Jimi Hendrix: Electric Church

Episode 1 | 1h 29m 15sVideo has Closed Captions

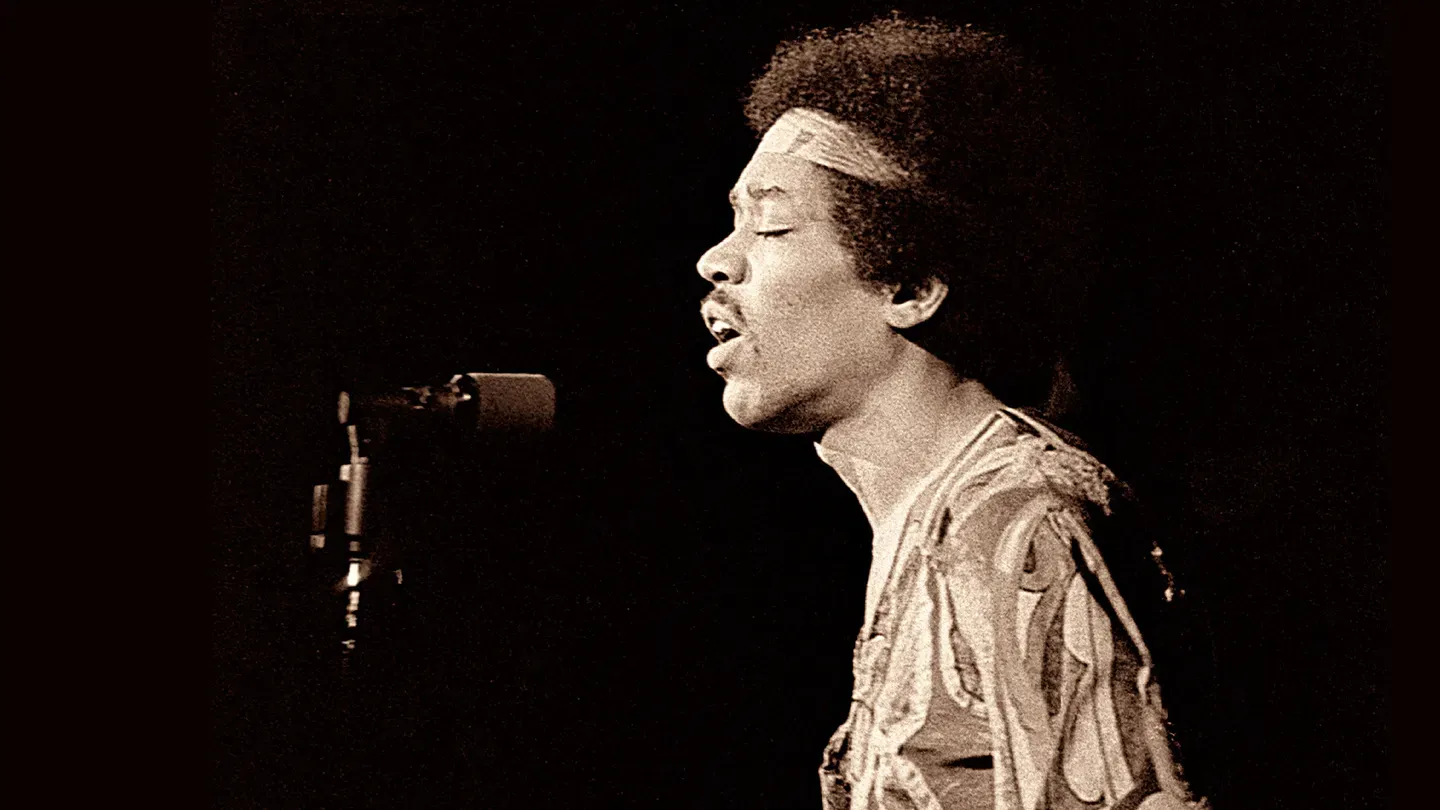

Experience the legendary guitarist’s unforgettable performance in Atlanta on July 4, 1970.

Trace the legendary guitarist’s journey to the Atlanta International Pop Festival and his unforgettable performance on July 4, 1970, captured in 16mm multi-camera footage. Hendrix drew nearly 500,000 people to his “Electric Church” for a concert that included “Purple Haze,” “Foxey Lady,” “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” “Hey Joe,” “Stone Free” and many more.

Jimi Hendrix: Electric Church

Episode 1 | 1h 29m 15sVideo has Closed Captions

Trace the legendary guitarist’s journey to the Atlanta International Pop Festival and his unforgettable performance on July 4, 1970, captured in 16mm multi-camera footage. Hendrix drew nearly 500,000 people to his “Electric Church” for a concert that included “Purple Haze,” “Foxey Lady,” “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” “Hey Joe,” “Stone Free” and many more.

How to Watch Jimi Hendrix: Electric Church

Jimi Hendrix: Electric Church is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipANNOUNCER: This program is available with Passport because of your generous donation to your local PBS station.

Thank you.

[cheering and applause] [guitarist noodling] [cheering and applause] [guitarist and drummer noodling] ANNOUNCER: Jimi Hendrix!

[cheering and applause] ♪ BILLY COX: Jimi Hendrix made every night a magical moment.

LESLIE WEST: The Atlanta Pop Festival had the greatest acts.

I mean, more than Woodstock.

BRUCE HAMPTON: It was amazing, bigger than Woodstock.

STEVE RASH: Three days of some of the most incredible music, from the Allman Brothers, B.B.

King, Bob Seger, Grand Funk Railroad, you never knew what was gonna happen next.

BOB MERLIS: This rock festival phenomenon was something really special.

ALEX COOLEY: I had to have Jimi Hendrix.

RASH: Somebody should shoot this thing.

It's gonna be big.

TERRY JOINER: 400,000 people, you can't control it.

STEVE CHEATHAM: It was July the 4th, and they were gonna hear "The Star Spangled Banner," by golly.

♪ KIRK HAMMETT: The way he performed, the way he wrote songs, the way he played his guitar.

♪ DEREK TRUCKS: Some people are bigger than the instrument they're playing.

Hendrix, he certainly falls in that category.

RICH ROBINSON: There weren't any boundaries with the way he played and the way that his playing made me feel.

STEVE WINWOOD: He was always pushing the envelope.

SUSAN TEDESCHI: He was the real deal, and he had star power.

♪ RASH: The 1970 Atlanta Pop Festival was the last of the great pop festivals.

COX: A little pecan grove in Atlanta was one of the places where he could have his sky church.

♪ JERREDEAN McDANIEL: All I heard about was the people taking their clothes off and jumping in the Echeconnee Creek.

[laughs] RASH: We were all making it up as we went along.

And the film sat undeveloped in my barn for 30 years.

[film projector running] MERLIS: Jimi represented a new freedom.

And the fact that Jimi was not afraid to be different put him out front, separate from his contemporaries.

He was one of a kind.

It was the most unique presentation of anybody in contemporary music, Black or White, at the time.

♪ You got me blowin', blowin' my mind ♪ ♪ Is it tomorrow ♪ ♪ or just the end of time?

♪ ♪ ♪ Oh, baby ♪ ♪ Oh, baby ♪ ♪ Yeah, purple haze ♪ MERLIS: There was an air of mystery about him.

We didn't know where he came from because no one else looked like that.

COX: Part of Jimi's appeal was the fact of the way that he dressed and he did not do a lot of interviews.

He did a few, but not in depth.

And that was a, a mystery about him because the way he carried himself, the way he smoked his cigarettes, the way he played his guitar and his movements onstage, which he had the, the whole ball of wax when it came to a unique guitar player.

MERLIS: If you think about the way he dressed, it was unique.

Totally different than his contemporaries.

People in blues and R&B like Muddy Waters, James Brown, Wilson Pickett, et cetera, they all had these very shiny, sharp suits.

Jimi's look was totally his own.

Nobody had anything going like that at all.

He was more than familiar with what we'd call the norm, having played with Little Richard, sat in with Wilson Pickett, Isley Brothers, and so on.

He knew what the convention was.

TEDESCHI: To me, he almost seemed like a movie star.

He was very charming.

You know, he was very handsome, very good-looking.

He had a confidence about him, a certain air.

And, you know, he just, you could tell he'd been through it.

PAUL McCARTNEY: He was finally coming in the front door, and I think his stint in England gave him the confidence.

We were all worshipping him.

How was he, how could he not have confidence?

ABE JACOB: The first awareness that I had of, of how big Jimi was becoming was the fact that the audiences got larger.

And by the end of that '68 tour, the places were packed and it was standing room.

MITCH MITCHELL: The initial thing in America of the two shows a night, um, you know, 49 cities in 52 days, which was just, you know, complete burnout territory.

We went from like, doing the sort of Fillmore or the small clubs, small theaters, to getting on the kind of stadium thing.

And then the festivals really kind of, um, started with loads and loads of acts on it.

JACOB: It was really only the, myself, the two roadies, uh, Gerry Stickells, uh, and a truck driver.

And, uh, one 19-foot rental van that carried everything.

Everything we did with Hendrix-- the musical instruments, the sound system, the guitars, uh, the merchandizing-- all fit in a 19-foot truck, uh, which leads me to my corollary that, uh, the amount of talent you have is inversely proportional to the number of trucks it takes to put your show on the road.

LARRY VAUGHN: We looked for the biggest buildings and the biggest cities because the demand for Jimi Hendrix tickets was that big.

We needed the biggest facilities.

EDDIE KRAMER: Yeah, Jimi was the big star.

He was the big kahuna.

He could command $100,000, which was a hell of a lot of money in those days.

JACOB: Jimi felt each of his concerts was a, a milieu as well as a spiritual experience.

And I think he wanted people to feel that they were either in his living room or later on, as he said, in a church, uh, and that we were experiencing this event together.

And when he was really onto that, there was an exciting exchange between, uh, the audience and the trio onstage.

♪ ♪ ♪ That's what the exciting part about a, a Hendrix concert was, was that it was a really give-and-take between him and the audience.

And I think that, I think the audience really felt that.

But I also think that's probably why the mystique of Hendrix is still here today was that those people that were fortunate enough to have seen him still remember the fact that, uh, they were part of the concert as well as, uh, being in the audience.

ROBINSON: That exchange is as potent as it gets.

DICK CAVETT: I heard you use the expression an electric church as an, as an ambition you had.

Was this speaking metaphorically or poetically or do you really want to... JIMI HENDRIX: Honestly, I don't know.

It's just a, it's just a belief that I have, you know.

It's, and it's, uh, we do use electric guitars.

Everything, you know, is electrified nowadays, you know.

CAVETT: Mm-hmm.

HENDRIX: So therefore the belief comes into, you know, through electricity to the people, whatever.

That's why we play so loud.

Because it doesn't actually hit through the eardrums, like most, uh, groups do nowadays.

You know, they say, "Well, we're gonna play loud, too, 'cause they're playing loud."

And they've got this real shrill sound, you know, and it's really hard.

We're playing for our sound to go inside the soul of the person, actually, you know, and see if they can awaken some kind of thing in their minds, you know.

'Cause there's so many sleeping people.

[chuckles] You can call it that if you want to.

How you doing?

You feeling alright?

[cheering] Yeah, right, there you go.

COX: I think the most important thing he was concerned about was people coming together and being a part of the music.

The sky church was the, the concept of maybe if you couldn't have the bleachers and et cetera, you could have them comfortably sitting under this humongous tent.

Like almost like a tent revival.

♪ Will I live tomorrow?

♪ ♪ Well, I just can't say ♪ ♪ Alright, now ♪ ♪ Oh, will I live tomorrow?

♪ ♪ Well, I just can't say right now ♪ ♪ But I know for goddamn sure ♪ ♪ I don't live today... ♪ TEDESCHI: I think people connect so strongly with Jimi because he really truly loved what he did.

And when you really love something that much and you have a gift and it comes out, it touches people.

VAUGHN: When Jimi Hendrix took the stage, there was a certain relationship that he had, it was almost transcendent.

Not only was he a fantastic guitar player, but it was almost like a spiritual experience going to one of his concerts.

♪ ♪ ♪ [cheering and applause] HENDRIX: Thank you, now.

Thank you very much.

Thank you very much.

COX: The people loved him.

They really loved this, his, his, his persona, the music, the songs.

And he could do nothing wrong.

ROBINSON: That purity of intention that he seemed to use to approach his music, his songwriting, his recording.

I mean, everything, I think that's what translated.

McCARTNEY: Just 'cause he was such a fine player.

You know, we all played guitar.

We all knew a bit.

You know, and, but he seemed to know more than us.

TRUCKS: In the light of day, the purity holds up.

The other stuff just does not.

It doesn't last.

When something's real, it's gonna last.

It's gonna last as long as people are listening.

HENDRIX: Music has a lot of influence on a lot of young people today, you know.

Politics are getting-- well, I don't know.

You know how they're getting.

You know.

A cat that talk on TV and a cat in Mississippi, a farmer in Mississippi can't barely understand him except when he says America.

You know.

So then he's gonna vote for him.

But through music, it's all true.

Either true or false, you know.

And like a, such a large gathering of people with music, it shows that music must mean something.

Before the times of King, Dr. Luther King, you know, there's been a whole lot of changes, but some people, after the, after the excitement or the backwash of the change slows down, they say, "Yeah, that was groovy.

Let's see, what else can we feast upon now?"

You know.

One of them things.

There's a whole lot of changes happening, but now it's time for all these changes to connect, to showing that it's leading up to love, peace, and harmony.

Matter of fact, what we're trying to stress also is like, music should be done outside in a festival type of way, just like they do it anywhere else.

Because a lot of kids from the ghetto or whatever you want to call it, you know, don't have enough money to travel across the country to see these different festivals, what they call festivals.

'Cause I'd like for everybody to see these types of festivals, how everybody mixed together.

You wouldn't believe it, you really wouldn't.

GLENN PHILLIPS: Atlanta was a very isolated city from the national music scene.

Not in terms of talent, but in terms of having connections to the music business.

ANTHONY DeCURTIS: This festival culture was beginning to develop.

There was a sense in which, wow, there's a lot of young kids who like this music.

RASH: Alex Cooley was the preeminent promoter in the southeast.

In Atlanta, he was the man.

COOLEY: We started hearing a radio station talking about the second Miami Pop Festival.

And it was all the groups I wanted to see, things that never came to Atlanta.

And I decided that's what I wanted to do with my life, so I came back to Atlanta and I put together a partnership with 17 guys.

We pooled our money and did the first Atlanta Pop Festival.

We didn't make money, but we did okay.

They all dropped away, that was enough.

And I, I kept doing it, and so I did the second Atlanta Pop Festival.

RASH: I think Alex knew that if he wanted to have a bigger success than the previous year, he needed a headliner.

Not just a popular artist.

Uh, not just an artist popular there in Atlanta.

He needed an international headliner.

DeCURTIS: There was nobody bigger than Jimi Hendrix at that point.

♪ Hendrix playing at a festival like that was a very significant event.

HAMMETT: Part of the power and part of the originality that, that Jimi had had to do with his vision.

He took a fairly pedestrian type of guitar that was primarily used by, like, surf bands and country musicians, and he turned it into a lethal weapon.

A very, very lethal weapon.

RASH: When Alex Cooley put together the pop festival in late May and June, um, our director of photography, John Butterworth, went to Alex and said, "Somebody should shoot this thing.

It's gonna be big."

And Alex said, "There's not much time," and John had said, "Well, we just happen to be in town, and we just happen to be in the business of shooting rock-and-roll music live."

And Alex said, "Oh, okay.

Do it."

HAMPTON: Counterculture started in the late sixties.

CHEATHAM: Well, it all centered around a coffeehouse on 14th and Peachtree called the Catacombs.

And it was mostly artists and musicians at first, and then it started attracting the intellectuals and the hippies and everybody else.

PHILLIPS: "The Great Speckled Bird" was an underground newspaper run basically by what would be called hippies of the era.

And it was sold on street corners, on, uh, Peachtree Street, other places throughout town, by hippies who would make a little money selling this paper.

And at the time, it was the way of spreading the word.

RICH FLOYD: "The Great Speckled Bird" was not viewed fondly by the police departments.

It was not viewed fondly by the established media.

The editorials and the content of "The Great Speckled Bird" pointed to, to the culture that was, that was becoming more and stronger daily, like a little army growing and growing.

PHILLIPS: "The Great Speckled Bird" was very important politically and culturally.

Although they started off as a political paper, what happened was the cultural aspects of this paper being tied in with these political aspects moved things forward a great degree.

HAMPTON: In Atlanta in '68 and '69, you know, there were 20,000 people in Piedmont Park and Peachtree Street, and they mostly had long hair or whatever.

[chanting] PHILLIPS: The scene in Atlanta was highly charged, and although civil rights and things had moved forward a great degree, it really was a very segregated city.

HAMPTON: Lester Maddox was governor, and there was no other character like him.

REPORTER: Three Negroes showed up at the Pickrick but were not allowed in.

Instead, Maddox accused them of trying to put him and his Negro employees out of a job.

MADDOX: You want these 40 people to lose their jobs right now?

MAN: You're distorting the gospel, number one.

MADDOX: Right.

Shut your big mouth.

[cheering and shouting] PHILLIPS: Lester Maddox, uh, had an ax handle that he carried at his restaurant to keep people that he didn't want to serve from coming in.

And it wasn't being sold as a Black and White issue.

Although coincidentally, these people that he didn't want to come in just coincidentally all happened to be Black.

It was being sold as this is about states' rights.

This is about me being able to serve who I want to serve.

MAN: The government gave you a decision.

Want do you want to do?

MADDOX: I'm not gonna integrate.

[cheering] I'll use ax handles, I'll use guns, I'll use paint, I'll use my fists, I'll use my customers, I'll use my employees.

I'll use anything at my disposal.

This property belongs to me, my wife, and my children.

It doesn't belong to anybody else.

I'll throw out a White one or a Black one or a redheaded one or a bald-headed one.

It doesn't make any difference.

HAMPTON: No one's open to change.

And it was a forced change, and certainly Jimi, with his music, there was nothing like that ever happening before.

PHILLIPS: When Hendrix first appeared in Atlanta in 1968, it was still a very segregated city.

[shouting and arguing] [whack] Jimi Hendrix became the performer that he was due to the visionary aspects of his art, sometimes overshadowed the visionary aspects of him in moving race relationships forward because he was an instrumental figure, much like Elvis in the fifties, in combining elements of culture in a way that was very appealing and non-threatening to people.

DeCURTIS: Hendrix had achieved a level of success that made him a target, certainly in parts of the culture that were pretty much still seriously segregated, regardless of what laws had passed.

PHILLIPS: He was interviewed by "The Great Speckled Bird."

And they asked him, "Do you get much into what's happening with Black people in regards to civil rights?"

They were asking.

And he said, "I don't get a chance, man.

I'm not thinking about Black people or White people.

I'm thinking about the obsolete and the new."

And that's what he was doing artistically.

And that carried over with his acceptance in a very big way to moving forward race relationships.

Had Hendrix been a politically centric figure, people would have seen that as threatening.

But he wasn't.

He combined these elements.

He brought them to people in a way that moved race relations forward.

MERLIS: In 1969 and 1970, Jimi Hendrix was the most important touring act in the world.

Keep in mind, the Beatles had stopped touring.

Dylan was in the wake of his motorcycle accident.

And really, if you were gonna put on a major event, you really had to have Jimi Hendrix.

It was kind of expected because he made the difference.

COOLEY: I had to have Jimi Hendrix.

To me, that was, that was the, the whole premise of the whole thing.

That's why I was in south Georgia, for God's sakes.

TERRY DEESE: Byron back in 1970 was just a real small country town.

I'm not sure we even had a red light in town.

If we did, it was just one.

FRANCES McDANIEL: Byron is named for Lord Byron, the poet.

It's on I-75, 100 miles south of Atlanta.

COOLEY: There was a racetrack there.

Right next to the racetrack was one of the most incredible pecan orchards you've ever seen.

Just beautiful.

JOINER: I was appointed the chief of police there.

And it was nobody but me.

PINCKNEY: Alex Cooley came down a couple two or three weeks before the pop festival.

He was extremely nice.

He came down and was explaining to us that they were gonna go out to the racetrack and that's where they were gonna hold it.

And it should not interfere with the town at all.

COOLEY: The owner of that property, he was a, a real character.

He, uh, he drank scotch and milk all day.

He would have done anything for the money.

I mean, he was desperate at this point, and I mean, he was also a moonshiner.

There was a still under the racetrack that produced gallons of moonshine a day.

So he was on our side, and he had some political influence, and so he paved the way partially.

But we, we almost did it by stealth.

MADDOX: Some visitors from all over the United States come in here with the idea that it's gonna be one of these uh, nasty, filthy, illegal activities.

And to the best of our ability and with all the adequate police power that we can man, we're going to see that the law is enforced in order to protect the lives and properties of the people, knowing full well that we'll have to pull in men that otherwise would be saving lives on Georgia's highways.

FRANK WADE: Governor Maddox was not in favor of having the festival at all.

He didn't like the music, didn't like the hippies.

Didn't like much of anything.

[laughs] JOINER: He was from the old school.

And he didn't want that kind of clientele in his state.

MAN 1: We understand it could be 200,000 or 300,000 people down there.

We know for a fact there's been 500 Coca-Colas ordered, so... MAN 2: 500... MAN 1: 500,000 Coca-Colas ordered for this meeting.

Uh, we don't think they'll all be drinking Coca-Colas.

JOINER: We woke up one morning, and cars were lined up on the interstate for miles trying to get off in Byron.

And I said, "Oh, my goodness, this is gonna be something else."

It turned out to be something else.

[laughs] DEESE: I guess it hit us all when everybody started showing up 'cause we'd heard some things on the news it was coming and nobody paid a lot of attention to it, until you go up that way and it's just people everywhere walking down the interstate.

Cars all parked on the side of the interstate.

Byron wasn't ready for what was coming to see us on that, that week.

FLOYD: The crowd, which probably swelled somewhere between 350,000 to 500,000, uh, in that neighborhood, had to have come from all across the United States.

JOINER: They were here from everywhere.

It wasn't as if it was just a crowd from Atlanta came down here or a crowd from Alabama or Washington.

I saw people and car tags from all over the United States here.

INTERVIEWER: What makes you come all the way from Dallas to a pop festival?

MAN: 'Cause, uh, I had a bunch of hassles in Dallas, and I knew that coming here, the type of people that would be here, there wouldn't be any hassles.

You know, you just kind of get away with it all and be with friends and everything.

Have a really good time.

FLOYD: $14 ticket for three days.

I mean, you can do the math.

That's a pretty good chunk of, uh, change to pay everybody for, for their efforts.

There was a fencing put around.

I think that it encompassed around 20 acres all the way around the, the field, the perimeter where people couldn't see in from standing outside and get a free view.

PINCKNEY: At first, you would see some real hippies.

But I think the thing I noticed most of all, it would be like a lot of college kids coming in.

And I mean, when they'd get out the cars, they'd just be college kids, all preppy-looking.

And then they would go through our bathrooms.

And when they came back out, you would not even recognize 'em.

McDANIEL: A lot of 'em were, uh, would come in the store and go in the bathroom, strip down, and put on next to nothing.

And we had never seen anything like that.

But they were there to have a good time.

FLOYD: You got the sense that, well, I think this is gonna be big, and then that Thursday and Friday, it just, you knew.

I mean, you knew it was just gonna be crazy big.

JOINER: It was just a humongous traffic jam, you know.

But I couldn't do anything about it.

We had to let 'em go where they wanted to go, you know?

RASH: You couldn't even depend on when the artist would arrive.

Not that they were late getting off the plane, there was no way to get them there.

All the roads were jammed.

COOLEY: Our transportation broke down, and we could not get out of the grounds.

And we had one helicopter that we had begged for, but it was not the kind of helicopter you would go to the Atlanta airport, pick up a performer, and bring back.

So there were some real adventures of people, different people getting to the stage.

RASH: That stage was so disorganized-- not disorganized, unorganized-- because everything was out of control.

Not, not that there wasn't a plan.

It just didn't happen because 500,000 people messed it up.

And remember, in those days, the technology didn't exist for the wireless headphones and the walkie-talkies and all of that.

It didn't exist.

And if someone couldn't reach someone by shouting across the stage, they didn't hear you.

Well, with 500,000 people next to you, nobody's gonna hear you 30 feet away.

BJ WADE: The people that were walking would just pile on, onto the hoods of the cars, the backs of the cars.

And that was the way people rode out there.

JOINER: I didn't have any other police officers.

And I had to run the whole thing myself.

And the little jail that we used was only two cells.

DEESE: That was the police department and also the court facilities at that time.

JOINER: We didn't come in here and harass 'em.

We stayed on the out-- on the perimeter, and watched them come and go as they pleased.

But we didn't just come out here and harass one or catch one smoking dope and hauled him off to jail, so we couldn't have done it.

It was too many of them.

PINCKNEY: They were selling tickets at first.

But so many people came that they just crashed the fence down, the gate.

WADE: And what began to happen locally was word began to get out what was going on at the racetrack.

First it was the local kids, of course.

They had to go, and they had to see.

But then the word got out that there were hippies, real hippies, that there were naked people running around out there, that there was all kind of stuff going on that we knew nothing about.

The traffic became even worse because now intermingled with ones trying to get to the festival were all the locals who had to go see what was going on.

McDANIEL: They just could not believe that such a thing happened in this sleepy little town of Byron.

WADE: People were completely shocked that people were taking their clothes off, that people were doing drugs out in the open.

And, of course, the music was something they had never heard before.

DEESE: We were out there practicing Little League baseball, and the preacher lived right there beside the church.

And he came out and called everybody to the pitcher's mound and, and told us that we need to all go home to our families because the hippies had taken over Vinson Valley.

And, you know, just all this fear of what was to come there.

And, of course, at that time, I was 16 and just had my driver's license and a couple of the guys loaded up with me, and we went straight to Vinson Valley to see what all the excitement was about.

JOINER: As long as they wasn't outside breaking the law somewhere, breaking in stores or houses, we didn't, we didn't bother 'em.

PINCKNEY: If you walked in there, you about got high from the smell of it.

WADE: It was very open.

It was very open.

Nobody was, you know, nobody was trying to act like they weren't selling or using.

PINCKNEY: And you could see anything in there.

Anything, if you catch what I'm saying.

MAN: When I was there Friday, I was separated from the other committee.

Um, I, I stopped a few minutes and watched a couple in the full throes of intercourse, right there on the path.

The, the girl was smoking a cigarette the whole time.

JOINER: At one point, I contacted one of the guys who was with the motorcycle gang that were called the, uh, Galloping Geese out of Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

And he agreed to help us patrol the city of Byron.

The hippies out here were very scared of the, the bikers at that time, so they helped us patrol the city of Byron at night on their motorcycles.

We paid 'em with a case of beer and a, a meal a day.

And, uh, we did not have one break-in the whole time.

FLOYD: The crowd remarkably did very well with the heat and the drugs that were consumed and the, and you have to admit they were there 'cause there were a lot of people walking around screwed up.

COOLEY: It scared the crap out of me.

I mean, I was really, truly frightened.

And I started thinking, "What the hell have I done here?"

JOINER: After a day or two, they were hungry.

And they started going into Byron and going through Dempsey Dumpsters, getting scraps, and begging folks for food.

And, of course, a lot of the local folks in Byron were cooking tubs of hot dogs and stuff and bringing them up here and selling 'em, and, uh, Coca-Colas and what have you.

WADE: Our local farmers took peaches and watermelons and, you know, things like that out there and just gave 'em away because they were hungry, there were too many people out there, they couldn't feed everybody.

MADDOX: We're deeply concerned because this comes on a holiday weekend, probably the most popular holiday weekend of the entire year.

JOINER: 104 degrees on July the 4th.

That's how hot it was on the day of the festival.

WEST: It was so freakin' hot.

I had everything I could do just to concentrate.

My hands were, you know, the sweat was pouring off my hands.

The guitar was getting sticky in my hands.

JOINER: The Byron Fire Department actually brought fire trucks up here and was spraying 'em down with the hoses to keep 'em cool.

A lot of 'em had heatstrokes and fell out with the heat.

We were wetting 'em down with the fire trucks.

They were down there swimming in the nude.

They were out here in the nude.

You know, just trying to stay cool.

I'd never seen nothing like it.

You know, people don't just walk around naked up here, you know.

To see all that, it was amazing.

And they didn't care.

They didn't, it didn't even bother 'em.

You know, they'd wave at ya.

"How ya doin'?"

They wouldn't care.

PINCKNEY: The people that were so against it... WADE: ...were down there looking, okay?

PINCKNEY: My lord, they were down there with binoculars and everything else.

I mean, you know, they wanted to be on the site.

But they were the ones that was, "Oh, it won't happen again.

It can never happen again."

WADE: They wanted to be able to talk about it for the rest of their lives.

MADDOX: I like festivals, and I like to have fun, but we want the people visiting down there to know that we expect them to abide by Georgia law.

WADE: Maddox flew over the area and declared it a disaster area.

He put out, I don't know, APBs or whatever you call them to tell people, don't go to Byron.

It's a total disaster area.

Parents, keep your kids home.

He was extremely upset that this was going on.

DeCURTIS: July of 1970, we're just a couple of months past the murders at Kent State, where protesting college students were shot to death on campus.

And in Jackson State in Mississippi as well.

People forget that there was a draft going on, uh, in 1970.

And so people who were over 18 and were males, they were pretty much sitting in the crosshairs.

DEESE: I was 16 and getting to where I had started thinking about the draft.

And I do think that is part of the lifestyle we were going through, that Vietnam was so deadly that, that this was part of the mindset of these young people.

You know, I'm not part of the establishment.

I'm gonna make up my own rules and do what I want to do.

COX: It was a very trying time with us being in the war.

Jimi and I went into the military just prior to Vietnam.

And that war was the real deal.

Larry Lee was our friend, and Larry Lee was wounded.

He had a plate in his head.

He got shot right on the verge of going into his brain.

And they mended that up.

So he got wounded there.

And, uh, so he was, he was very fortunate that he didn't die.

But it was a reality for us.

And it affected him, and it affected us because he was our friend.

MERLIS: The Atlanta Pop Festival was the largest U.S. audience he ever played to.

RASH: The backstage scene was very confused.

You didn't know who was gonna actually be there at what time.

Uh, oh, Hendrix is here.

Phew!

Thank God!

You know, it's the July 4th.

It's got to be Hendrix.

HAMPTON: Jimi Hendrix landed at the pop festival at 10:00 in a helicopter.

And there were no lights there to see.

And I think he got onstage about 12:30.

RASH: When Jimi came onstage, only the people immediately in front of the stage could see him.

Power was the big issue because Georgia rural power only had a certain amount of generating capability in middle Georgia.

And they couldn't provide enough lights to light the stage, the audience, and provide the backstage facilities as well, so we had to pick and choose.

Someone made the choice in, in the lighting crew that they didn't want the audience to watch the bands set up.

They wanted to have a visual entrance.

In the dark, you really couldn't tell how many there were.

But you could see the cigarette lighters going to the horizon.

We knew that there were a lot of people.

Uh, there was no way to count them.

ANNOUNCER: Jimi Hendrix!

[cheering and applause] HENDRIX: Like to introduce a new member to the group.

It's Billy Cox on bass.

And Mitch Mitchell on drums.

[cheering and applause] And yours truly on public saxophone.

MIKE NEAL: Jimi would pretty much walk out on stage, tune the guitar, they'd chat among themselves and then okay, hit the chords for the first tune.

And that was how the show started.

It was very primitive.

Everything was very personal.

You just had a guy with a guitar.

And he had to make the good people... [unclear] And Jimi was one of the guys who could do it.

COX: The cheers, the claps, the, the noise that they made was incredible.

And it kind of, it kind of gave us an edge.

♪ ♪ Alright, baby, dig this ♪ ♪ We gotta talk to you ♪ ♪ Talk to you in a second ♪ ♪ You don't care for me ♪ ♪ I don't a-care about that ♪ ♪ You got a new fool, yeah ♪ ♪ I like it like that ♪ ♪ I have only one itching desire ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your fire ♪ ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your fire ♪ ♪ Hey, let me stand, baby ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your fire ♪ ♪ Oh, let me stand ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your fire ♪ ♪ Let me stand, baby ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your fire ♪ ♪ Listen here, baby ♪ ♪ And stop acting so damn crazy ♪ ♪ You say your mom ain't home ♪ ♪ It ain't my concern ♪ ♪ Just play with me, child ♪ ♪ and you won't get burned ♪ ♪ I have only one itching desire ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your ♪ ♪ ♪ Let me stand, please ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your fire ♪ ♪ Let me stand ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your fire ♪ ♪ Uh-huh ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your fire ♪ ♪ Oh, move over, Rover ♪ ♪ And let Jimi take over ♪ ♪ Yeah, you know ♪ ♪ what I'm talking about, baby ♪ ♪ Yeah ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ You try to gimme your money ♪ ♪ You better save it, babe ♪ ♪ Save it for your rainy day ♪ ♪ I have only one itching desire ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your ♪ ♪ ♪ Oh, let me stand, baby ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your fire ♪ ♪ Oh, let me stand ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your fire ♪ ♪ I ain't gonna do too much harm ♪ ♪ Let me stand next to your fire ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ [cheering and applause] ♪ Really hope it isn't too loud for you.

[applause] 'Cause if it is, we could always turn it up.

♪ ♪ ♪ It's very far away ♪ ♪ It takes about a half a day to get there ♪ ♪ ♪ It's not in Spain, baby ♪ ♪ But all the same ♪ ♪ you know, it's a groovy name ♪ ♪ And the wind's just right ♪ ♪ ♪ Hang on, my darling ♪ ♪ Hang on if you want to go ♪ ♪ Whole lot of fun, yeah ♪ ♪ Don't let it get to your head too much ♪ ♪ Spanish Castle magic ♪ ♪ Watch out, baby ♪ ♪ The clouds are really low ♪ ♪ And they overflow with cotton candy ♪ ♪ Yeah, but sometimes battlegrounds ♪ ♪ of red and brown ♪ ♪ But it's all in your mind, baby ♪ ♪ Don't waste your time ♪ ♪ thinking about bad things ♪ ♪ Just get your little mind around ♪ ♪ ♪ Hang on, my darling ♪ ♪ Hang on if you want to go ♪ ♪ Whole lot of fun sometimes ♪ ♪ Don't let it get to your mind, say ♪ ♪ Spanish Castle magic ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ Hang on, my darling ♪ ♪ ♪ Hang on if you want to go ♪ ♪ ♪ Whole lot of fun, yeah ♪ ♪ Don't let it get to your head, say ♪ ♪ Spanish Castle magic ♪ ♪ ♪ Little bit of Spanish Castle magic ♪ ♪ ♪ Whole lot of fun, you know what I mean?

♪ ♪ Even said all your prayers, brother ♪ ♪ But don't let it get nasty, baby ♪ ♪ Don't let it get nasty ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ [cheering and applause] ♪ ♪ ♪ There must be some kind of way out of here ♪ ♪ ♪ As I was saying ♪ ♪ There must be some kind of way out of here ♪ ♪ Said the joker to the thief ♪ ♪ There's too much confusion ♪ ♪ I just can't get no relief ♪ ♪ Businessmen, they drink my wine ♪ ♪ Plowmen, dig my earth ♪ ♪ None will level on the line ♪ ♪ Nobody offered his word ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ No reason to get excited ♪ ♪ The thief, he kindly spoke ♪ ♪ There are many here among us ♪ ♪ Who feel that life is but a joke ♪ ♪ But you and I, we've been through that ♪ ♪ And this is not our fate ♪ ♪ So let us stop talkin' falsely now ♪ ♪ The hour's getting late ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ All around the watchtower ♪ ♪ Princes kept the view ♪ ♪ While all the servants came and went ♪ ♪ Barefoot servants, too ♪ ♪ Outside in the cold distance ♪ ♪ Wildcats did growl ♪ ♪ Two riders were approaching ♪ ♪ And the wind began to howl ♪ ♪ ♪ Gotta get away ♪ ♪ Gotta get away from here ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ MAN: Alright, Jimi!

[cheering and applause] HENDRIX: I'd like to say thank you very much for the last four years.

And also dedicated to the girl over there with the purple underwear on.

♪ ♪ ♪ You know you're a cute little heartbreaker ♪ ♪ Foxey ♪ ♪ ♪ And you know you're a sweet little lovemaker ♪ ♪ ♪ Foxey ♪ ♪ ♪ I want to take you home ♪ ♪ I won't do you no harm ♪ ♪ You've got to be all mine, all mine ♪ ♪ Ooh, foxey lady ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ I see you are down on the scene ♪ ♪ Foxey ♪ ♪ ♪ You make me want to get up and scream ♪ ♪ Foxey ♪ ♪ ♪ I've made up my mind ♪ ♪ ♪ I'm tired of wasting all my time ♪ ♪ ♪ You've got to be all mine, all mine ♪ ♪ Ooh, foxey lady ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ I'm gonna take you home ♪ ♪ ♪ I won't do you no harm ♪ ♪ ♪ You've got to be all mine ♪ ♪ ♪ Ooh, foxey lady ♪ ♪ ♪ Foxey lady, yeah ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ [cheering and applause] I want everybody to stand up and get off your, your thing and stand up on your feet 'cause we're gonna do a happy birthday song to America.

And it goes something like...

This is the thing we were brainwashed into singing at school.

Let's all, everybody stand up and sing it together, with feeling.

[plays opening of "The Star Spangled Banner"] [segues to "Purple Haze"] ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ Purple haze all in my brain ♪ ♪ Lately things just don't seem the same ♪ ♪ I'm actin' funny but I don't know why ♪ ♪ 'Scuse me while I kiss the sky ♪ ♪ ♪ Purple haze all around ♪ ♪ Don't know if I'm comin' up or down ♪ ♪ Am I happy or in misery?

♪ ♪ Whatever it is ♪ ♪ that girl put a spell on me ♪ ♪ ♪ Help me ♪ ♪ Forget about it, baby ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ Purple haze all in my eyes ♪ ♪ Don't know if it's, uh, day or night ♪ ♪ You got me blowin', blowin' my mind ♪ ♪ Tomorrow or just the end of time?

♪ ♪ ♪ Help me ♪ ♪ Forget about it, baby ♪ ♪ Yeah, take me away, babe ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ [cheering and applause] Thank you very much.

We're loving the fireworks, y'all.

I'd like to say thank you very much for staying.

And next time I'd like to see you again soon.

♪ [cheering and applause] ♪ ♪ ♪ Hey, Joe ♪ ♪ Where you goin' with that gun in your hand?

♪ ♪ ♪ Hey, Joe ♪ ♪ I said, where you goin' ♪ ♪ with that gun in your hand?

♪ ♪ ♪ I'm goin' down to shoot my old lady ♪ ♪ You know I caught her ♪ ♪ messin' around with another man ♪ ♪ ♪ Yes, I'm goin' down to shoot my old lady ♪ ♪ You know I caught her messin' around ♪ ♪ with another man ♪ ♪ And you know that ain't too cool ♪ ♪ ♪ Hey, Joe, hey, Joe ♪ ♪ I heard you shot your woman down ♪ ♪ ♪ Hey, hey, hey, Joe ♪ ♪ I heard you shot your woman down ♪ ♪ ♪ Yes, I did, yes, I did ♪ ♪ You know I caught her messin' around ♪ ♪ messin' around town ♪ ♪ I told you, man ♪ ♪ ♪ Yes, I did, yes, I did, yeah ♪ ♪ Yes, I caught her messin' around town ♪ ♪ I gave her the gun and I shot her ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ Hey, Joe, hey, Joe ♪ ♪ Where you gonna run to now?

♪ ♪ ♪ Where you gonna run to?

♪ ♪ Hey, Joe ♪ ♪ Where you gonna run to now?

♪ ♪ ♪ I'm goin' way down south, way down south ♪ ♪ Way down to Mexico way ♪ ♪ ♪ I'm goin' way down south, way down south ♪ ♪ Way down where I can be free ♪ ♪ ♪ Hey, hey, hey, Joe ♪ ♪ Lord, can I come along with you, babe?

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ [cheering and applause] I hope America has about a million more of these kind of birthdays.

You can have concerts and so forth for everyone.

Thank you very much and good night.

♪ MAN: No!

Come on!

Stay with us!

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ Well, I stand up next to a mountain ♪ ♪ I chop it down with the edge of my hand ♪ ♪ ♪ Well, I stand up next to a mountain ♪ ♪ I chop it down with the edge of my hand ♪ ♪ ♪ Well, I pick up all the pieces ♪ ♪ and make an island ♪ ♪ Might even raise a little sand ♪ ♪ ♪ Yeah ♪ ♪ 'Cause I'm a voodoo child ♪ ♪ Lord knows I'm a voodoo child, baby ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ I didn't mean to take up all your sweet time ♪ ♪ I'll give it right back one of these days ♪ ♪ ♪ I didn't mean to take up all your sweet time ♪ ♪ I'll give it right back one of these days ♪ ♪ ♪ If I don't see you no more in this world ♪ ♪ Lord, if I don't see you no more ♪ ♪ in this world ♪ ♪ I'll be joining the next world ♪ ♪ Don't be ♪ ♪ Don't be late ♪ ♪ I'm a voodoo child ♪ ♪ ♪ Lord knows I'm a voodoo child ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ [cheering and applause] Thank you very much for staying.

Thank you.

[cheering and applause] AUDIENCE: More!

More!

More!

More!

More!

More!

More!

More!

More!

More!

More!

More!

[chanting continues] [cheering and applause] Thank you very much.

You all are very kind.

[plucking guitar] You know, if I could see you, we could get together, but that light is blinding me, man.

It's hard to play when you can't see nobody, you know?

Now I can see you.

Yeah, right.

Uh-uh-uh-uh!

We're gonna do a thing called "Stone Free."

We hope you remember that one.

♪ ♪ ♪ Every day of the week ♪ ♪ I'm in a different city, y'all ♪ ♪ If I stay too long ♪ ♪ the people try to pull me down ♪ ♪ They talk about me like a dog ♪ ♪ Talk about the clothes I wear ♪ ♪ But they don't realize ♪ ♪ they're the ones who's square, baby ♪ ♪ Yeah, that's why ♪ ♪ you can't pull me down ♪ ♪ I don't want to be tied down ♪ ♪ I got to move on ♪ ♪ Yeah!

♪ ♪ Stone free ♪ ♪ to do what I please ♪ ♪ Stone free ♪ ♪ to ride the breeze ♪ ♪ Stone free ♪ ♪ I can't stay ♪ ♪ I got to, got to get away ♪ ♪ ♪ Listen here, baby ♪ ♪ A woman here, a woman there ♪ ♪ try to keep me in a plastic cage ♪ ♪ They don't realize it's so easy to break ♪ ♪ Yeah, but sometimes I can feel my heart ♪ ♪ kind of running hot, you know what I mean?

♪ ♪ That's when I got to move ♪ ♪ before I get caught ♪ ♪ I don't know, but that's why ♪ ♪ You can't hold me down ♪ ♪ I don't want to be tied down ♪ ♪ I got to move on ♪ ♪ Yeah, I said stone free ♪ ♪ to do what I please ♪ ♪ Stone free ♪ ♪ to ride the breeze ♪ ♪ Stone free ♪ ♪ I can't stay, I ♪ ♪ got to get away ♪ ♪ ♪ Turn me loose, baby ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ Stone free ♪ ♪ to do what I please ♪ ♪ Stone free ♪ ♪ to ride the breeze ♪ ♪ Stone free ♪ ♪ I can't stay ♪ ♪ I got to keep movin', got to get away ♪ ♪ Stone free ♪ ♪ I'm gonna leave right now ♪ ♪ ♪ Stone free ♪ ♪ I gotta get on out, baby, yeah ♪ ♪ Stone free ♪ ♪ Got to keep moving ♪ ♪ [playing "The Star Spangled Banner"] [cheering and applause] ♪ [fireworks exploding] ♪ [fireworks exploding] ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ [fireworks exploding] ♪ ♪ ♪ [fireworks exploding] ♪ ♪ [fireworks exploding] ♪ ♪ [fireworks exploding] ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ Have you heard, babe ♪ ♪ ♪ What the wind's blowin' round ♪ ♪ ♪ Have you heard, babe ♪ ♪ ♪ What the wind's been blowin' all down ♪ ♪ ♪ Communication, yeah ♪ ♪ is comin' on strong ♪ ♪ ♪ Yeah, we don't give a damn ♪ ♪ Lord, if your hair is short or long ♪ ♪ ♪ I said get out of your grave ♪ ♪ Everybody is dancing in the street ♪ ♪ ♪ Don't be slow, do what you know ♪ ♪ They gotta practice what they preach ♪ ♪ ♪ It's time for you and me ♪ ♪ Yeah, to face reality ♪ ♪ ♪ Forget about the past, baby ♪ ♪ Things ain't what they used to be ♪ ♪ Go straight ♪ ♪ ♪ Go straight ahead, baby ♪ ♪ ♪ Go straight ahead ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ You got to tell the children the truth ♪ ♪ They don't need a whole lot of lies ♪ ♪ ♪ When you give them love ♪ ♪ You better give it right ♪ ♪ You better give them love right ♪ ♪ 'Cause one of these days ♪ ♪ they'll be running things ♪ ♪ Better give it to the young and old ♪ ♪ ♪ Go out your house, baby ♪ ♪ Power to the people ♪ ♪ Pass it on, pass it on to the young and old ♪ ♪ ♪ Keep on straight ahead, babe ♪ ♪ ♪ Keep on straight ahead, now ♪ ♪ ♪ Hello, my friend ♪ ♪ I'm so happy to see you again ♪ ♪ But I was so sad ♪ ♪ I was all by myself ♪ ♪ I just couldn't make it ♪ ♪ All by myself, baby ♪ ♪ I couldn't make it alone, baby ♪ ♪ ♪ Have you heard?

♪ ♪ [cheering and applause] Thank you very much and good night.

[cheering and applause] RASH: At the end of Jimi's performance, the audience started cheering, of course, and chanting "We want Jimi.

We want Jimi."

And then they wouldn't stop.

FLOYD: They had endured a long, hot day on July 4th, and it was the most uplifting thing I've seen in show business in many, many years.

And they were there and the love was there for Jimi Hendrix.

I mean, that's, there's no doubt about it.

COX: Jimi got a lot of energy from that particular gig.

He played-- "All Along the Watchtower" was in the wrong key.

And, uh, so he started off, ♪ Da da da da da ♪ Then in the middle he said, well, not the middle, maybe about two bars, he says, "As I was saying."

And when I heard "As I was saying," I said, I know he's in the wrong key.

So he's got to be going to, to the right key.

Then it was ♪ da da da da ♪ and we rocked.

So after the gig was over, he says, "Man, you were on me like white on rice."

I said, "No, I was on you like a rat on cheese."

So he laughed at that.

He just, that was very funny.

JOINER: He actually put on a real show and it, the people that were here, they, they loved it, you know.

COX: After the gig, I said, he, he came up to me and said, "You know, these songs are gonna be okay because these people never heard 'em, and they're clapping and jumping around."

I said, "Yeah, that's great."

You know, evidently maybe we're producing, trying to produce some good stuff.

You know, so that, that was, that was incredible.

HAMPTON: Jimi Hendrix played what he felt.

And right before he went on, there were ten people interviewing him for "The Great Speckled Bird."

He said, "It's great to play for these people.

They want to hear me."

THOMAS DOUCETTE: It was something.

When you really got next to it like that, it was something.

And I'd been next to a lot.

I mean, you know.

I mean, I saw Coltrane play before he died.

You know?

All kinds of things.

I mean, Jimi was... Hey, man, come on, he was Jimi Hendrix.

TRUCKS: I mean, there's, there's this stage show, there's this persona that's coming out, but there's really, there's no smoke and mirrors.

I mean, there's no, nobody's BSing anybody.

Like this is, this is people that know what they're doing and at the highest level and getting it done.

ROBINSON: And the music was incredibly emotive and also drew emotion from people.

And so that exchange is as potent as it gets.

HAMMETT: For me, there really hasn't been anyone since that's had the impact that Jimi Hendrix has had on, on, on music.

WINWOOD: It was honest music.

He wasn't trying to fool anyone.

He was...

It was, it was from the heart, and it was what he believed.

COOLEY: 4th of July, Jimi Hendrix's "Star Spangled Banner," it knocked people's socks off, as they say.

DOUCETTE: They're shooting off fireworks.

And he's playing to the fireworks.

It was gorgeous, man!

It was unbelievable.

It was beautiful.

It was Jimi.

WADE: Until the Olympics happened, this was the largest crowd for anything that had ever happened in the state of Georgia.

MERLIS: It's noteworthy that the Atlanta Pop Festival's in the deep South at a time when it was thought that the South was hostile to rock-and-roll, to hippies, people who looked like that.

But the reality was the world had changed by that time.

The long-hair ethos was embraced by kids in the South as much or if not more so than kids in the North.

RASH: When the festival was over, we all knew that we had something important on film.

We didn't know whether or not it would be accepted as important.

You have to remember, in 1970, the authorities were really cracking down on festivals in general and us hippies.

And it was becoming a difficult thing to sustain.

We all knew instinctively that this innocence was over.

We didn't know what was to come, but we knew that it was over.

And I guess we all felt that this is probably the last one.

Turned out it really was.

JOINER: When the festival was over, it was the worst trashed-out place you've ever seen in your life.

I mean, there was trash all the way from Vinson Valley Lake down there where they were swimming all the way to Byron.

All this field out here was just solid trash.

WADE: The racetrack itself, that whole area, it was totally, totally just the biggest mess you've ever seen in your life.

Even though at some point sometime during the festival, they had tried to clean up, you know, it still, by the time everybody left... PINCKNEY: It was such a mess.

WADE: Just too many people, not enough restrooms, not enough places for them to eat.

Um, so, yeah, it was, it was, that area was totally trashed.

DEESE: I remember the trash 'cause everywhere, when we'd go up through there, everywhere there was people, it seems like now there was trash bags and clothes and just stuff that they had discarded and left.

And it took several weeks to get all of that cleaned up.

FLOYD: I was disappointed in the disregard that the counterculture had for the environment.

I mean, I thought that that was part of what the counterculture would have done a better job at.

And, and, and it showed me that when you get into certain situations, you don't always act responsibly.

But it wasn't the first time I'd seen that.

I mean, Woodstock wasn't left a sea of green grass when they left there either.

PHILLIPS: I will say that I had a feeling about that this might be sort of the beginning of the end.

Things were getting a little darker in terms of drug use, prevalence of drug use, harder drugs.

You could see things were going in another direction.

And of course, all this has been documented, what happened at Altamont and all these things.

So you could see the culture changing a little bit.

So in terms of Atlanta and this gigantic festival, this was, and certainly in retrospect, sort of the end of an era.

And, and a great end to an era.

I mean, it was a, a powerful moment.

And I felt, uh, really lucky to be there and be taking part in it.

And as they grew and became bigger and bigger, it became inevitable that they would become more and more regulated.

And that did change them.

MERLIS: Atlanta Pop was a moment in time.

These giant festivals became so unwieldy, they could never happen again.

FLOYD: I think pop festivals in general took on a, a risk factor far greater than investors or backers or organizers wanted to move forward with after the Atlanta Pop Festival.

Maybe the time had come and gone, and maybe it was frozen, if you will, or not, or not, uh, not meant to happen again.

[laughs] RASH: In 1970, there were no other ancillary markets.

Videotape, videocassette, DVDs-- none of that had been invented.

If you didn't make that first summer's marketing window, you were dead.

So no one was interested in releasing the film the next year.

So the film sat for 30-some odd years in my barn, undeveloped.

MERLIS: If you think about the time at which, uh, Jimi, uh, performed at the Atlantic Pop Festival, it was the apogee of his professional career.

He was working on a new album, just finishing it.

He had opened his studio in New York, Electric Lady.

And he was on top of the world in terms of being the most dominant force in popular music.

And who would ever have imagined that the world would lose him a short time after that.

♪ ♪ Here comes Dolly Dagger ♪ ♪ Her love's so heavy, gonna make you stagger ♪ ♪ Dolly Dagger ♪ ♪ She drinks her blood ♪ ♪ from a jagged edge ♪ ♪ ♪ Aw, drink up, baby ♪ ♪ ♪ Been riding broomsticks ♪ ♪ since she was 15 ♪ ♪ Blow out all the other ♪ ♪ witches on the scene ♪ ♪ She got a bullwhip ♪ ♪ just as long ♪ ♪ as your life ♪ ♪ Her tongue can even scratch the soul out ♪ ♪ of the devil's wife ♪ ♪ Well, I seen her ♪ ♪ in action at ♪ ♪ the players' choice ♪ ♪ Turnin' all the love men into donut boys ♪ ♪ Hey, red-hot mama... ♪