The Presidents: Reagan (Part 2)

Season 10 Episode 11 | 1h 53m 50sVideo has Audio Description

Ronald Reagan left the White House one of the most popular presidents of the 20th century.

The second part of Ronald Reagan, who left the White House one of the most popular presidents of the 20th century — and one of the most controversial.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate sponsorship for American Experience is provided by Liberty Mutual Insurance and Carlisle Companies. Major funding by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

The Presidents: Reagan (Part 2)

Season 10 Episode 11 | 1h 53m 50sVideo has Audio Description

The second part of Ronald Reagan, who left the White House one of the most popular presidents of the 20th century — and one of the most controversial.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch American Experience

American Experience is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

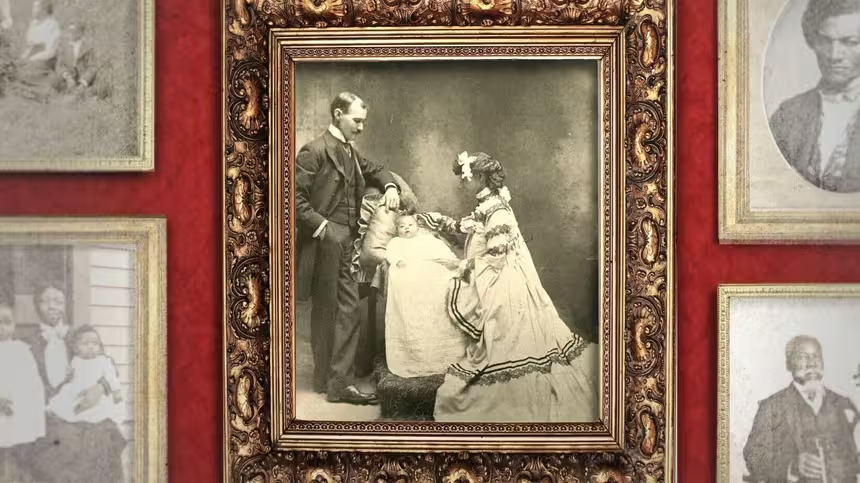

When is a photo an act of resistance?

For families that just decades earlier were torn apart by chattel slavery, being photographed together was proof of their resilience.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

In this award-winning collection, explore documentaries, biographies, interviews, articles, image galleries and more for an in-depth look at the history of the American presidency.

Video has Audio Description

Part of the award-winning The Presidents collection. (2h 16m 40s)

Video has Closed Captions

Part of the award-winning "The Presidents" collection. (1h 52m 37s)

The Presidents: Reagan (Part 1)

Video has Audio Description

A biography from American Experience's collection of presidential portraits. (1h 50m 17s)

Video has Audio Description

Part of the award-winning The Presidents collection. (1h 50m 37s)

Video has Audio Description

A look at the US vice presidency, from constitutional afterthought to position of political import. (52m 36s)

Video has Closed Captions

Part of the award-winning The Presidents collection. (2h 47m 5s)

Video has Audio Description

Part of the award-winning The Presidents collection. (1h 44m 52s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ ANNOUNCER: Previously on "Reagan"... MORRIS: He had a picture in his office and he would say... (imitating Reagan): "You see, that's where I used to be a lifeguard.

DALLEK: Reagan loved the hero's role because he fantasized himself as a heroic figure.

(gunfire) As of now, I am a candidate seeking the Republican nomination for governor.

I like the way he takes a firm stand on things.

He's the hope of America.

They see him as an honest man.

As someone who speaks his mind.

SMITH: People took a chance and they voted on a Hollywood movie actor.

(clapping) It is time for us to realize that we are too great a nation to limit ourselves to small dreams.

MEESE: Most people don't remember now, but that was probably the worst economic situation the United States had been in since the Great Depression.

ANDERSON: You couldn't buy gasoline, no matter how much money you had.

Interest rates were going up, people couldn't afford to buy homes.

And the Soviet Union was getting away with murder internationally.

We've come to a turning point.

I will propose budget cuts in virtually every department of government.

O'NEILL: He and I don't agree on his plan whatsoever.

If you make over $50,000, then you're for the Republican plan because that's who it's geared for.

SMITH: There are very few conventional politicians who would have stuck it out as he did.

He never gave up, he just kept right on going.

And it didn't crush him.

(gunshots) MATTHEWS: Here's a guy who had survived a very deadly shot of an assassin.

It was big stuff.

I mean you're talking about Hollywood drama here.

RON REAGAN: He's a guy who's almost impossible to dislike.

And yet, he has almost no close friends.

ANNOUNCER: The conclusion of "Reagan"-- tonight on "American Experience."

(crowd applauds) DEMONSTRATORS (chanting): Demokracja!

Demokracja!

Demokracja!

NARRATOR: In 1981, Reagan saw a chance to strike at the heart of the Soviet empire.

DEMONSTRATORS: Demokracja!

NARRATOR: The Polish workers' movement Solidarity marched for democratic freedoms.

When the government declared martial law, Reagan was determined to keep Solidarity alive.

DEMONSTRATORS: Solidarnosc!

NARRATOR: He met Pope John Paul II a few months later, in June 1982.

Like Reagan, the Polish pope had also survived an assassin's bullets in 1981.

He, too, believed God had spared him for a special mission.

The pope would turn the Catholic Church in Poland into an underground Solidarity network.

Reagan imposed economic sanctions and committed the C.I.A.

to undermine the government and keep Solidarity alive.

(crowd singing) NARRATOR: If Poland were freed, they felt all Eastern Europe would follow.

(explosions) NARRATOR: Other covert actions were less peaceful.

(men yelling) NARRATOR: In Afghanistan, Reagan continued President Carter's policy of backing the factions fighting a Soviet invasion.

♪ ♪ In Central America, the C.I.A.

began to train forces to harass the Sandinistas, the Soviet-backed government in Nicaragua.

The "Contras" became one of Reagan's favorite causes.

(people shouting and cheering) NARRATOR: By 1982, many Americans thought Reagan's weapons buildup was madness.

It energized a movement to freeze production of nuclear weapons.

Reagan's crusade was against communism; the freeze movement's was against the bomb.

(drums beating) ♪ ♪ Use of the bomb, scientist Carl Sagan warned, would doom the earth to a "nuclear winter"... a fate more likely, Reagan's opponents felt, with yet more bombs in the hands of the man who pacified Berkeley with bayonets.

(crowd clamoring) ROBERT DALLEK: Well, they saw him as something of a cowboy.

They identified him with Barry Goldwater, who, in the 1964 campaign, says we should think about lobbing one into the men's room of the Kremlin, you see.

People would... had bumper stickers in 1964.

The Goldwater bumper sticker was "In your heart you know he's right," and the opponent's said, "In your heart you know he's nuts," seeing him as a dangerous character who might provoke a nuclear war.

And Reagan was seen by many people as the heir of that rhetoric, and he frightens people.

(chanting, drums beating) ROBERT McNAMARA: But the stocks of both Warsaw Pact and NATO have been increasing dramatically.

The deployments have been increasing.

More and more one hears of the necessity of developing plans for fighting and winning nuclear wars-- inconceivable to me, madness.

It is precisely a freeze which would stop the further buildup of weapons aimed at our country.

I think the freeze is both in the mutual interest of our two countries and is certainly verifiable.

I reject the absurd theory that we can have fewer nuclear bombs tomorrow only if we build more nuclear bombs today.

MAN: We are the people.

We want no more nuclear weapons.

(applause, cheering) NARRATOR: By the spring, the freeze had grown into an enormous grassroots movement.

A freeze resolution was introduced in Congress.

On June 12, nearly one million Americans rallied in Central Park to send a message to Ronald Reagan.

♪ ♪ In July 1979, Reagan had visited the Air Defense Command deep under Cheyenne Mountain in Colorado.

The trip reinforced his aversion to the conventional wisdom of the nuclear age... that there is no defense against a missile attack... only the threat of retaliation.

MARTIN ANDERSON: On the plane coming home, I was discussing this with Reagan.

He said, look, the president has two bad choices.

If a nuclear missile is fired at the United States, you can either do nothing-- let the missile land and explode and kill a lot of people-- or you can retaliate.

When you're told the missile is coming in, you've got ten, 15 minutes before it hits.

So you'd push your own button and punish the aggressor-- you know where the missile's coming from-- and maybe set off a nuclear war between the United States and Soviet Union, and have an Armageddon to destroy most of our civilization.

He said both choices are bad choices.

There has to be another way, and we need to really explore the whole question of missile defense.

NARRATOR: The most controversial initiative of his presidency reflected the Ronald Reagan who had faith in America and in his own ability to rescue and to prevail.

I call upon the scientific community in our country, those who gave us nuclear weapons, to turn their great talents now to the cause of mankind and world peace, to give us the means of rendering these nuclear weapons impotent and obsolete.

Let me share with you a vision of the future which offers hope.

It is that we embark on a program to counter the awesome Soviet missile threat with measures that are defensive.

NARRATOR: To Reagan, defense was a moral imperative... but a daunting task to those who had to work out the details.

Perhaps there would be satellites in space with computer-guided lasers that would zap enemy missiles.

Most scientists dismissed Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative, or S.D.I., as unworkable.

He was known to have a rich imagination.

(lasers zapping, bombs exploding) I think Ronald Reagan really believed in S.D.I.

I think he had this view that, I mean, it was like the way he used to talk about events that had actually happened in the movies as if they really had happened.

I think he was like, you know, "Star Wars"-- the movie.

All right, Haydon, focus that inertia projector on them and let them have it!

NARRATOR: The "Star Wars" in which Reagan starred was filmed in 1939.

What is it?

The inertia projector.

It's a device for throwing electrical waves capable of paralyzing alternate and direct currents at their source.

(movie music playing) MAN: The inertia projector.

It not only makes the United States invincible in war, but in so doing promises to become the greatest force for world peace ever discovered.

NARRATOR: It was sometimes difficult for Ronald Reagan to distinguish fantasy from reality.

LOU CANNON: He believed in this so strongly that he began to think that S.D.I.

was in existence when it wasn't even on the drawing board.

That's... he so passionately, passionately wanted... wanted there to be a nuclear defense.

In a loose way, it was a religious notion of the City of God surrounded by an inviolable barrier.

The weapons of the heathen will bounce off our shield and shatter into fragments.

We will be inviolable here beneath this shield.

"Shield," "shield"... he used the word "shield" a lot.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Reagan presented S.D.I.

as a benign shield.

The soothing rhetoric may have disguised another motive.

I think President Reagan saw S.D.I.

as being yet another pressure on the Soviets-- something that they could not withstand-- and I think he was right.

Whether it would work or not, it was a heck of a challenge to the Soviet empire, which was having a very difficult time competing economically and otherwise.

The first reaction was really frightening.

I mean, people were just enormously frightened by, uh... by that program.

In part, I think, because it probably revealed, in their minds, the impossibility for the Soviet Union to really compete in that area because of our technological inferiority at that time.

NARRATOR: S.D.I.

became an expensive research project.

Reagan's dream of making missiles obsolete was for the future.

He still had to cope with their threat.

Before he took office, the Soviet Union had deployed highly mobile missiles that could wipe out Western Europe in minutes.

NATO had decided to counter them with a new generation of U.S. missiles, but also to negotiate limits on all the missiles.

Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, who had little interest in negotiating, suggested a negotiating position: If the Soviets pulled out all their missiles, NATO would not deploy any new ones.

This so-called "zero option" was a very hard line.

Reagan bought it.

WEINBERGER: The president said that that would be very good if we could get that, and I said, "Yes.

"One of the arguments you're going to hear, Mr. President, "is that the Soviets will never agree to this, "and therefore we shouldn't even propose it, because that means we can't get an agreement."

Why should the Soviets have any incentive to remove what they already had in place?

And the whole arms control community-- the professional arms controllers-- believed strongly that this was unfair.

It would be unfair, unjust to ask the Soviets to do this.

Besides, everyone knew that the Soviets had this fundamental sense of insecurity, so we shouldn't exacerbate that sense of insecurity.

That's exactly what Reagan wanted to do, was to exacerbate the feeling of insecurity.

It was very simple.

NARRATOR: The face that Reagan showed the world early in his term was that of his hawkish advisers, provocative and uncompromising.

REAGAN: The United States is prepared to cancel its deployment of Pershing 2 and ground-launched missiles if the Soviets will dismantle their SS-20, SS-4, and SS-5 missiles.

This would be an historic step.

With Soviet agreement, we could together substantially reduce the dread threat of nuclear war which hangs over the people of Europe.

REPORTER: Mr. President, what are the chances the Soviets will accept your proposals?

It was took as a joke.

Nobody in his right mind thought of the possibility of zero option.

No.

We... at that time, we thought that we would be able to make a deal.

We'll keep part of the... our missiles.

We'll somehow split Europe and the United States.

It was always in the cards, this big game, say, um... to make some division between European... major European countries and the United States, playing on their fears of nuclear war, you know, this winter, nuclear winter or some awful scenarios.

(demonstrators chanting, drumming) NARRATOR: The Soviets sought to exploit legitimate European anxieties of a nuclear war fought on the soil of Europe, already bristling with nuclear weapons on both sides.

Demonstrators marched for a nuclear-free Europe.

If they succeeded, the NATO alliance, which had held together for 32 years to thwart Soviet advances, would be in shambles.

MAN: This may be... this may be the greatest political meeting ever held in this country.

NARRATOR: Reagan arrived in Great Britain as NATO's crisis escalated.

MAN: Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. President Reagan.

NARRATOR: In his speech to Parliament, he went beyond the missile debate to highlight his broader goals, the crusade of his lifetime.

What I'm describing now is a plan and a hope for the long term: the march of freedom and democracy, which will leave Marxism-Leninism on the ash heap of history, as it has left other tyrannies which stifle the freedom and muzzle the self-expression of the people.

MARGARET THATCHER: "The ash heap of history."

Hitler had been dispatched to the ash heap of history.

And if you look at that whole sentence, he was saying that our purpose is that these tyrannies, as past tyrannies, should be consigned to the ash heap of history.

He was right.

Let us now begin a major effort to secure the best-- a crusade for freedom that will engage the faith and fortitude of the next generation.

For the sake of peace and justice, let us move toward a world in which all people are at last free to determine their own destiny.

Thank you.

NARRATOR: As he preached his message of freedom and built up America's defenses, Reagan avoided talking to the Russians.

But he knew that would change.

GEORGE SHULTZ: He wanted to engage with the Soviets.

You kind of got the impression from a distance that he didn't, that he just wanted to be militarily strong, and that was it.

But that wasn't it at all.

He could see, as a good negotiator that you negotiate effectively when you're strong, but also that your strength erodes unless you use it.

As a negotiator, he didn't want to just stand on strength.

NARRATOR: But Reagan seldom took the initiative.

He has been compared to a Turkish pasha, awaiting overtures from his advisers.

In February 1983, Secretary Shultz asked if he wanted to talk to Ambassador Dobrynin.

And he said, "Wonderful."

And that set off a big fight inside the White House, because his staff didn't want him to do that.

I think that they didn't want to have these discussions and they didn't have as much confidence in him as I did.

But he just smiled and brushed them off and said, "Bring him over," and I did.

NARRATOR: Reagan pushed human rights with Dobrynin, urging him to help with the emigration of Russian Pentecostals, Christian dissidents who had been living in the basement of the American Embassy in Moscow for almost five years.

A few months later, they were allowed to leave the country.

♪ ♪ SHULTZ: And the deal was, "We'll let them out if you don't crow," and Ronald Reagan never said a word.

It was the first deal he made, but it was unknown and I think it was impressive to the Soviets because it showed them, number one, he kept his word, even though it was very tempting politically to trumpet what he had done; and number two, it showed them that he really cared about human rights.

(applause) (band playing "Onward, Christian Soldiers") NARRATOR: It was not Reagan the negotiator but Reagan the crusading ideologue who addressed evangelical supporters a few weeks later.

Congress was about to vote on the freeze resolution, which could jeopardize his deployment of missiles in Europe, and Reagan was about to give his most controversial speech.

REAGAN: So in your discussions of the nuclear freeze proposals, I urge you to beware the temptation of pride, the temptation of blithely declaring yourselves above it all and label both sides equally at fault, to ignore the facts of history and the aggressive impulses of an evil empire, to simply call the arms race a giant misunderstanding, and thereby remove yourself from the struggle between right and wrong and good and evil.

Let us be aware that while they preach the supremacy of the state, declare its omnipotence over individual man, and predict its eventual domination of all peoples on the Earth, they are the focus of evil in the modern world.

(applause) (band continues playing "Onward, Christian Soldiers") MAN: People recoiled in horror.

They said, "Can't talk this way."

Reagan said, "I'm doing it on purpose," because the whole thrust of detente had been to demoralize-- de-moralize-- our foreign policy.

Ronald Reagan wanted to remoralize it.

Let's tell them that we think they are thugs and that they are a focus of evil in the modern world, and let's get the American people back into the Cold War as a moral...

I'll say it, crusade.

He saw a lack of freedom.

He saw social degradation.

He hated what he saw.

He at least understood and was courageous enough to articulate to the rest of the world that what there is over there is despicable.

It's evil.

One of the oldest words in any language-- evil.

This was the rhetoric of the 1950s, that you cannot have compromise with evil.

You cannot have compromise with a Soviet system that is intent upon our destruction.

And Reagan is harking back to this early Cold War rhetoric and thinking, you see, and people find it frightening, they find it chilling.

MAN: The danger we face today warrants laying aside all other matters, even staying in session day and night if that's required.

The dangers are great.

And therefore, any negotiations that could be started, I'm for.

MAN: You're going to be the only administration going back to the '50s that either did not negotiate a treaty with the Soviets or met with them.

So be it.

I don't think we want to get ourselves in the position where we don't want to be the only administration that didn't make an arms control agreement, and therefore let's go make one.

That's no way to approach it.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Early in the morning of September 1, 1983, a Korean airliner strayed into Soviet airspace.

(explosion) It was shot down, with the loss of 269 lives.

"Newsweek" wrote, "The world witnessed the Soviet Union that Ronald Reagan had always warned against."

(demonstrators shouting, chanting) REAGAN: This was the Soviet Union against the world and the moral precepts which guide human relations among people everywhere.

It was an act of barbarism born of a society which wantonly disregards individual rights and the value of human life, and seeks constantly to expand and dominate other nations.

NARRATOR: Reagan's rhetoric was tough, but when Weinberger urged him to break off arms talks with the Soviets, he resisted.

He sided with Shultz, who urged him to remain engaged.

In the Kremlin, the rhetoric was also harsh.

The Soviets compared Reagan to Hitler, called him mad.

The question for Soviet leader Yury Andropov was how to engage Ronald Reagan.

MORRIS: The latter months of 1983, when Andropov had to come to terms with the knowledge that he was a dying man, plus the knowledge that Ronald Reagan was a much more formidable adversary than had originally been assumed-- that he was not an old, stupid ideologue, that he was actually a very canny and determined warrior-- the combination of these two realizations, these two perceptions on Andropov's part, brought about, I believe, the selection of Mikhail Gorbachev to be his successor.

Andropov started grooming Gorbachev in 1983 as the only likely Soviet leader who would be able to handle this formidable, adamantine anti-communist on the other side of the Atlantic.

(air raid sirens blaring) (explosion) NARRATOR: On November 20, 1983, 100 million Americans watched "The Day After," a television movie which portrayed the effects of a nuclear war on Lawrence, Kansas.

(explosion roars, people scream) Reagan saw a preview.

"It was a scenario," he wrote, "that could lead to the end of civilization as we knew it."

The film aired on the eve of the deployment of American missiles in Germany.

The inveterate optimist confided: "It left me greatly depressed."

But, undeterred, Reagan dispatched the missiles to Europe on schedule.

♪ ♪ Reagan's goal was to negotiate from strength.

The deployment of I.N.F.

missiles in Germany, particularly, but Britain and Italy, too, showing the strength and cohesion of the NATO alliance, was a Cold War turning point.

You have to have... show the strength before you can have effective diplomacy.

WILL: There's a whole generation of people who were always haunted by the prospect that our amiable, undisciplined democracy wouldn't have the staying power.

It would just get outlasted.

We said, "Well, maybe they're just tougher than we are, and stupidity armed with discipline will win after all," uh, and that was what was at issue in the early 1980s, was whether or not democracies would crack.

If NATO had decided upon a deployment and had then been unable to follow through on it, the Soviet Union would have had a new burst of confidence, the Atlantic alliance would have been cracked, and who knows what would have happened?

It didn't turn out to be the case in large measure, again, because the president was staying the course, internationally as well as domestically.

♪ ♪ The present round of the negotiations is discontinued... ...bez ustanavleniya kakovo-libo sroka vozobnovleniya.

Without any date set for their resumption.

NARRATOR: Soviet delegates walked out of the arms control negotiations.

For the first time in more than 20 years, there were no superpower talks.

HELEN THOMAS: Senator Byrd says that our relations with the Soviet Union have reached the lowest point in 20 years.

And six eminent world leaders today said that we're headed for global suicide.

What are you going to do about it with this arms race?

I don't think we are, and I don't think we're any closer, or as close as we might have been in the past, to a possible conflict or confrontation that could lead to a nuclear conflagration.

NARRATOR: Some in the Kremlin also worried about Reagan's intentions.

TARASENKO: First Deputy Foreign Minister Korniyenko asked me to come to his office.

He showed me a Politburo paper informing us that the United States have plans all prepared and in place for first strike against the Soviet Union, with, uh... first priority to destroying all command center and structures of the country.

And Korniyenko asked me to... to prepare some paper which would send a signal that, uh... we know about these plans and we will not be caught unprepared.

NARRATOR: When Reagan read intelligence reports indicating the Soviets had feared a first strike, he turned to his national security adviser, Bud McFarlane, and said, "Do you suppose they really believe that?

"I don't see how they would believe that.

But it's something to think about."

Later that day, he worried about Armageddon.

MAN: When he talked about it, he would be genuinely anguished and would physically withdraw and lean forward and, uh... with quiet passion... oh... explain his fear that Armageddon was at hand, and that unless he tried to move us away from this incredible nuclear threat of each other, that it could happen in his lifetime, and he was determined to do something about it.

NARRATOR: But Reagan had something to cheer about.

In 1983, after 16 months of recession, Americans slowly went back to work.

Spurred by tax cuts, lower inflation and government spending, the economy began to improve.

The recovery would turn into an unprecedented boom that lasted for eight years.

In 1984, the president could campaign on America's renewed confidence.

ANNOUNCER: It's morning again in America.

Today, more men and women will go to work than ever before in our country's history.

With interest rates and inflation down, more people are buying new homes, and our new families can have confidence in the future.

America today is prouder and stronger and better.

Why would we want to return to where we were less than four short years ago?

MAN: We'd come through the... the darkness of the night.

We'd come through the economic crises and the recession of '82.

We're now to a point where we'd rebuilt the defenses of the country.

Uh, the military basically felt good about themselves again, which they clearly didn't in 1980.

The American country felt good about itself again, which it clearly didn't in 1980.

Of course it was "morning in America"-- they were running the biggest deficits in history and pouring stimulus into the economy, and everybody was happy and nobody was afraid.

So the middle class...

The minute the middle class in this country no longer fears unemployment, it gets very, very conservative.

When it fears unemployment, it identifies with poor people, because it says, "We're next."

But as long as they figure "we're next to get rich" in the time of a boom, they're very conservative.

(crowd cheering, band playing) NARRATOR: As he had in 1980, Reagan would reach out to blue-collar workers.

His appeal amazed his opponents.

MATTHEWS: He didn't know anybody by name.

He didn't even know his own HUD secretary, Sam Pierce.

He called him "Mr. Mayor" when he met him one time.

I mean, a man like that, who is so unfamiliar with the individuals he has to deal with, you would think was an idiot.

But he wasn't, because Ronald Reagan knew one person, and I don't know who this person is-- maybe I've never met him-- but this person is the American people.

CROWD (chanting): U.S.A.!

U.S.A.!

U.S.A.!

U.S.A.!

U.S.A.!

U.S.A.!

MATTHEWS: Even though Ronald Reagan lives in Bel Air and he hangs around with the Bloomingdales, somehow he still evokes the guy that goes to the Knights of Columbus and plays cards on Friday night.

That guy who struggles every day just to make it through the week, who worries about never having a vacation, who's afraid he might get sick and lose his health insurance-- that guy thought Ronald Reagan was his guy, thought Ronald Reagan was looking out for him.

That's an amazing power.

But he knew who he was talking to, and he talked to them.

CROWD (chanting): Four more years!

All right-- I'm willing if you are.

(cheering) ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Things were going well until one August day at his ranch.

REAGAN: All right, my fellow Americans, I'm pleased to tell you today that I've signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever.

We begin bombing in five minutes.

(men chuckling in background) NARRATOR: That gaffe before an open mike helped Reagan's opponent.

What a day!

Nice to meet you.

Win in November.

Good, thank you.

NARRATOR: Former Vice President Walter Mondale appealed to voters worried about Reagan's hard line toward the Soviets.

He opposed every agreement by Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter-- every one of them-- to control nuclear armaments.

He has conducted an arms race on Earth and now he wants to extend it to the heavens.

RICHARD WIRTHLIN: The public generally felt a little more comfortable with the way Walter Mondale described how he would negotiate than they did with Reagan's peace-through-strength platform, because they could not really see at that juncture how peace could be realized through strength.

NARRATOR: A campaign ad tried to explain.

ANNOUNCER: There is a bear in the woods.

For some people, the bear is easy to see.

Others don't see it at all.

Some people say the bear is tame.

Others say it's vicious and dangerous.

Since no one can really be sure who is right, isn't it smart to be as strong as the bear... if there is a bear?

NARRATOR: How close to get to the bear had been an issue for almost four years.

Reagan's key White House advisers who had opposed dealing with the Soviets had either left or been eased out by Nancy Reagan as she maneuvered behind the scene.

When Reagan invited Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko to pay a visit before the election, Nancy was delighted.

"For years," she wrote, "it had troubled me that my husband was always portrayed as a warmonger."

NANCY REAGAN: Andrei Gromyko came up to me and said, "Does your husband believe in peace?"

and I said, "Well, of course."

And he said, "Well, then, um... Will you whisper that in his ear every night?"

And I said, "Yes, I will, and I'll whisper it in your ear, too."

(laughs) NARRATOR: The meeting helped defuse one of Mondale's campaign issues.

But a few days later, Reagan's age, 73, became an issue.

In his first television debate, he seemed confused.

We have... our military... the morale is high.

The...

I think the people should understand that two-thirds of the defense budget pays for pay... and... salary... or pay and pension.

NARRATOR: Nancy blamed Reagan's staff and wanted to fire Richard Darman, who she felt had swamped Reagan with too many facts.

MAN: You already are the oldest president in history.

And some of your staff say you were tired after your most recent encounter with Mr. Mondale.

I recall yet that President Kennedy had to go for days on end with very little sleep during the Cuban missile crisis.

Is there any doubt in your mind that you would be able to function in such circumstances?

Not at all, Mr. Trewhitt, and I want you to know that also I will not make age an issue of this campaign.

I am not going to exploit for political purposes my opponent's youth and inexperience.

(laughter) (applause and cheering) ("Hail to the Chief" playing) NARRATOR: The age issue would not go away... but Reagan routed Walter Mondale with 59% of the vote.

"We can read," Tip O'Neill would later tell him.

"In my 50 years in public life, I've never seen a man more popular than you with the American people."

CANNON: If there's one constant in American presidential politics, it's that landslides are poison to the winner.

I mean, Roosevelt's landslide, he packs the Supreme Court.

Johnson's landslide, we go to war in Vietnam, you know.

Nixon's landslide, we have the Watergate cover-up.

Landslides are just murderous for the winner.

I mean, because there's so much power in that place, if you give a guy and you say he's won everything and "I've carried every state except Minnesota," then you've got to look out.

CROWD (chanting): Four more years!

Four more years!

(crowd whooping) I think that's just been arranged.

(loud cheering) ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: In the next four years, Reagan would see his best days as president and his worst, without the help of his oldest advisers.

His troika was burned out.

Michael Deaver, who had been with Reagan since he became governor, would soon leave government.

Edwin Meese, who had been with him just as long, left to become attorney general.

Chief of Staff James Baker became treasury secretary, switching jobs with Don Regan, who became the new chief of staff.

But the opportunities of the second term were apparent within weeks.

Reagan had written to Leonid Brezhnev in 1981, suggesting they meet when the climate was better.

(funeral march playing) NARRATOR: Brezhnev died the next year.

In 1983, he had written Yury Andropov of his interest in eliminating the nuclear threat.

That year ended with a heightened threat.

Then Andropov died.

At 4:00 a.m. on March 11, 1985, Reagan was awakened to be told that Konstantin Chernenko had died.

"'How am I supposed to get anyplace with the Russians,' I asked Nancy, 'if they keep dying on me?'"

(men speaking Russian) The new man in the Kremlin, Mikhail Gorbachev, was not about to die on anyone.

He was 54 years old, vital, alert, intelligent... and a reformer.

He would try to make the communist economy more productive and the political system more open.

Margaret Thatcher had met Gorbachev and been impressed.

THATCHER: I like Mr. Gorbachev.

We can do business together.

We both believe in our own political systems; he firmly believes in his, I firmly believe in mine.

We're never going to change one another.

But we talked and we discussed freely.

Now, that was what we wanted.

This was what President Reagan had been wanting in the battle of ideas.

So I said, "Look, this man is prepared "to meet argument with argument.

"That's a totally new phenomenon.

So we really can do business and perhaps get somewhere."

NARRATOR: As soon as Gorbachev came to power in March, Reagan proposed a meeting.

It would lead to his greatest achievements.

In June, he confronted terrorism.

His response would threaten his presidency.

MAN (over radio): They are beating the passengers, they are beating the passengers.

They are threatening to kill them now.

NARRATOR: Terrorists hijacked a plane and murdered an American passenger.

This crisis was resolved, but it heightened Reagan's concern for seven other Americans held hostage in Beirut.

They had been kidnapped by followers of Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini, who had held American diplomats hostage and helped undermine Jimmy Carter's presidency.

Reagan took a firm stand on not dealing with terrorists.

Let me make it plain to the assassins in Beirut and their accomplices, wherever they may be, that America will never make concessions to terrorists.

To do so would only invite more terrorism.

NARRATOR: But Reagan heard how William Buckley, his C.I.A.

station chief in Beirut, had been beaten by his captors.

As he personalized the plight of the hostages, the importance of his policy tended to fade.

REPORTER: ...terrible mistake to link the seven hostages to the 39?

I don't think anything that attempts to get people back who have been kidnapped by thugs and murderers and barbarians is wrong to do.

And we're going to do everything we can to get all of them back that are held in that way.

(applause) WILL: This is the soft side of Ronald Reagan.

He was really bothered by the hostages.

It would take a harder man than Ronald Reagan to say what a president ought to say, which is, "I'm sorry, this is a big country "and big countries have casualties, if you will, "and we just have to regard those people "as, for the moment, casualties.

Put them out of your mind."

Ronald Reagan had a hard time being hard.

NARRATOR: In July 1985, five days after an operation for colon cancer, Reagan was asked by his national security adviser, Bud McFarlane, to approve a secret plan.

It was time to improve relations with Iran by courting moderates who might succeed the Ayatollah Khomeini and who might influence their followers in Beirut to release the seven captive Americans.

McFARLANE: His reaction was that, yes, if we could open a dialogue with people who might succeed Khomeini, that would be good.

When the possibility of the release of the hostages was added, he was even more enthusiastic.

NARRATOR: Reagan soon approved a shipment of arms to Iran which he would later deny was a trade for hostages.

That wasn't all he would deny.

"I didn't have cancer," he later told reporters.

"Something inside of me had cancer, and it was removed."

♪ ♪ The next month, he was at the ranch, ready to saddle up.

(chuckling) It was a constant argument to try to convince him, no, he could not ride as he wanted to ride.

MAN: Finally the elapsed time is over and the first lady protectively says, "Well, let's start off gently and we'll just walk our horses around the ranch."

The next day, he went out to ride, and there's a stretch where you have a nice straightaway.

Because the doctor would be in a vehicle behind us and a lot of places we'd go, the vehicle couldn't be in eyesight, so he'd kind of, "Well, if he's not looking, we can do it.

I won't tell, will you?"

And I heard this yell up in front from several people and I... so we put it into gear and rode up closer and all we could see was the dust from the hoof beats in the distance as the president galloped away from the crowd.

(laughing) But he was something.

No way in hell were you going to stop that man from riding.

And it was fine.

♪ ♪ HUTTON: One of the agents next to me says, "Doc, the first lady wants you down in the barn."

And as I walked down there, everybody else is walking away, which wasn't customary, and I said, "Gee, what's... what's... what's in store?"

She says, "Now, John," she says, "you stand here.

"We're going to have a little meeting, but we're not all here yet."

(Nancy Reagan laughing) Yep, ever the protector.

NARRATOR: Three months later, Ronald Reagan would have another summit-- in Geneva.

(band playing march) Ronald Reagan had warned that the Soviets cheat and lie.

He had opposed every arms deal American presidents had made with the Soviets in the 1970s, but he arrived in Geneva in November 1985 confident that he could handle the new leader of the evil empire.

SMITH: Conservative Republicans for 50 years had tended to denigrate the importance of personal diplomacy.

It's the legacy of the Yalta conference, and they thought F.D.R.

had sold us out, and then we sold out China-- we were always selling out someone, and the sale was usually by a president who thought that if only he could get in a room with his Soviet counterpart, that his charm and his arguments would prevail.

That's the conservative tradition, and yet Reagan clearly believed that he could do that, that the force of his personality and of his arguments and above all, of his sincerity would impress themselves upon the Soviets.

NARRATOR: Secretary Weinberger was less sure.

His letter urging Reagan not to hamstring S.D.I.

was leaked to the press and seen as an effort to sabotage the summit.

(band continues playing) Mikhail Gorbachev, general secretary of the Communist Party, came to Geneva to negotiate with the man Yury Andropov had considered impossible, called mad, compared to Hitler.

The vigorous 54-year-old whose charming smile was said to hide teeth of iron had come to meet the 74-year-old president who had railed against communism for almost 40 years.

I felt a strong fear, a palpable sense of fear throughout the delegation that this young, formidably intelligent, aggressive Soviet leader was going to run rings around our gentle, slow, slightly doddery, aging president.

The American delegation was afraid that he was going to be outsmarted, outmaneuvered and diplomatically, perhaps, destroyed.

(camera shutters clicking) REPORTER: What's the... what's the first priority?

Peace.

(siren blaring) And I see it now in memory in slow motion.

It was supremely dramatic.

This great, gleaming black Zil comes whispering around the corner, on the gravel, crunches to a halt.

Down the stairs comes this great, gliding, blue-suited, unbelievably self-confident and calm president without a coat on, in the freezing air.

And out of the big, black Russian limousine comes this awkward, short, rather dumpy, heavily overcoated, heavily scarfed, hatted Communist leader who fumbled with his scarf and fumbled with his coat as he approached this great, benign presence.

And they met at the foot of the stairs.

Reagan towered over Gorbachev.

Gorbachev looked up into Reagan's face-- looked at him very intensely.

Reagan smiled down at him and then gently choreographed him up the stairs.

TARASENKO: Gorbachev's in standard Politburo hat, standard Politburo overcoat.

It reminds me of the K.G.B.

agent from bad American films.

(laughs) So I said to myself that we have lost the first... this photo opportunity.

We have lost this first round.

NARRATOR: "When the delegations met," Reagan recalled, "I took Gorbachev through the long history "of Soviet aggression.

"I wanted to explain why the free world had good reason to put up its guard against the Soviet bloc."

MORRIS: His language was brutal.

He would say things like "Let me tell you, Mr. General Secretary, why we fear you and why we despise your system."

Now, that, in a diplomatic meeting, is extremely confrontational language.

Prezident... s pervoi minuty... INTERPRETER: The president from the very start started to speak in a kind of lecturing tone, as though I was a suspect or maybe a student.

And I cut him short.

I said, "Mr. President, "you are not a prosecutor; I'm not the accused.

You are not a teacher; I am not a student."

MORRIS: But Reagan somehow was able to say things like that, but at the same time, he seemed to have a sweetness and a benign quality about him that neutralized, or at least took the edge off, what from Richard Nixon would seem like a declaration of war.

NARRATOR: To ease the tension, Reagan suggested they talk in private.

As they walked to a less formal house by the lake, they chatted about Reagan's movie career-- the first time they had talked as human beings.

BESSMERTNYKH: Gorbachev immediately started to like Reagan.

That was a very surprising thing.

I think Reagan had something which was so dear to Gorbachev, and that is sincerity.

This human vision and human touch-- and when he talked with our leaders, he talked very emotional.

And he came across-- this is a human being.

He is trying to explain himself to you.

So maybe for the first time, our leaders started to think that on the other side it's not a machine, it's not some robot.

RON REAGAN: I think that people don't reckon with the power of charm and just personal persuasiveness.

And, you know, when my father kind of turns the high beams on, uh, even, even somebody like Gorbachev tends to melt.

NARRATOR: As they walked back to rejoin their delegations, Reagan invited Gorbachev to Washington.

Gorbachev reciprocated with an invitation to Moscow.

♪ ♪ On the second day, Reagan found Gorbachev ready to talk about "building down" their arsenals, but determined to kill S.D.I.

Reagan resisted.

Gorbachev was visibly irritated.

He said, "Why you are repeating "the same and the same thing to me?

"I've heard that many times.

"Stop this rubbish.

Tell me something more."

It was literally so.

It was a harsh discussion.

NARRATOR: But at the end, the mood was warm.

Reagan left Geneva with S.D.I.

intact and an agreement: a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.

The world breathed a sigh of relief.

There was another communiqué-- to Hussein Aga Khan and his parents.

"Dear Friends, on Tuesday I found one of your fish dead "in the bottom of the tank.

"I don't know what could have happened, "but I added two new ones (same kind).

"I hope this was all right.

"Thanks for letting us live in your lovely home.

Ronald Reagan."

SERGEANT AT ARMS: Mr. Speaker, the president of the United States.

SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE: The president of the United States.

(cheering and applause) NARRATOR: "I haven't gotten such a reception since I was shot," Reagan would quip.

The image of Ronald Reagan as a trigger-happy cowboy had begun to fade.

(cheers and applause continue) ♪ ♪ In October 1986, Reagan met Gorbachev for the second time in a hastily called summit at Reykjavik, Iceland.

Once again, his conservative backers-- now largely out of government-- were worried he would seek an arms agreement just for the sake of an agreement.

NOFZIGER: I said, "Well, Mr. President, "I'm here because there's a lot of people worried "that you're going to go to Reykjavik and give away the store."

And he said, "Lin...," he said, "Linwood"-- because he always called me Linwood, which is not my name-- he said, "Linwood, I don't want you ever to worry about that."

He said, "I still have the scars on my back from when I fought the communists in Hollywood."

He said, "Don't ever worry about it."

Proterpite!

NARRATOR: Gorbachev had his own problems.

He needed an arms agreement.

He could not manage both economic reform and the arms race, especially S.D.I.

He would try his best to make Reagan give away the store.

I didn't know you were here.

TARASENKO: Propose to him a package beyond all the expectation.

To talk real big, see, that was his idea.

"Why... we shall discuss all these small things?

Let's come up with a big idea... and sell it."

NARRATOR: Gorbachev offered Reagan everything he had wanted.

They would both destroy half their long-range bombers and missiles, eliminate all the missiles threatening Europe, and he made a major concession on human rights.

SHULTZ: They agreed for the first time that human rights would be a legitimate, recognized, regular item on our agenda.

They agreed to that.

That was a breakthrough, and with all due respect to the arms control breakthroughs, when you are breaking through on the nature of the relation between a government and its people, you're really getting a lot deeper than perhaps you think.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: "Gorbachev," Secretary Shultz wrote, "laid gifts at our feet."

The delegations worked all night to iron out the details of his proposal.

♪ ♪ REPORTER: Are you making headway at least?

I won't comment on that now.

NARRATOR: The next morning, Gorbachev insisted that all the missile reductions he proposed were contingent on restricting S.D.I.

research to the laboratory.

Reagan refused.

The meeting appeared to be over.

He wanted to get out of there and be home.

He wanted to be home for dinner that night if at all possible, and with the change in hours, if he left in the early afternoon, he could be home in Washington for dinner.

And... matter of fact, I remember his talking to me about that, saying, "Don, these things are really dragging on."

And I had to say to him, "Hang in there, Mr. President, I think we're winning."

REPORTER: Mr. President, have you made any real progress, sir?

We're not through.

Are you going to meet again, sir?

Yes.

NARRATOR: At this point, the Soviets challenged the Americans to make a concession.

The U.S. delegation did.

It agreed to abide by the treaty banning space defenses for ten years, and proposed that during that time, both sides scrap all, not just half, their long-range missiles.

Reagan liked the boldness of the proposal.

Reagan responded with the idea of having the complete elimination of strategic ballistic missiles.

And Gorbachev said, "How about eliminating all the nuclear weapons instead of just going part by part?"

They actually moved each other to the direction of the discussion of the complete elimination of nuclear weapons.

♪ ♪ They were carried away.

The two gentlemen were carried away with the historic ideas they had presented to each other.

TARASENKO: It's easy to say that President Reagan was anti-communist or anti-something.

No, he was a romantic.

As I later on judged, he really was maybe the last romantic of this generation.

Gorbachev also had a romantic abolitionist vision of nuclear weapons.

You've got the two leaders of these two powerful countries running way beyond their arms controllers and their defense ministries and their state departments, and saying, "Let's get rid of nuclear weapons."

There was a time-out asked by the American side, and Gorbachev walked out, and we were sitting in a small room and he said, "If Reagan accepts, the world... will be a new one.

Things will change historically."

NARRATOR: Reagan could realize his dream of reducing the nuclear threat, perhaps only by risking his dream of a space defense.

Gorbachev still insisted on restricting S.D.I.

research to the laboratory.

MAN: The president needed to understand.

He needed information in a very tense situation.

When asked, I expressed the categorical view that there was no way you could see the program through to a successful conclusion if we accepted the constraints that Gorbachev had in mind.

Upon hearing that, he turned to Don Regan and said, "If we agree to this, won't we be doing that simply so we can leave here with an agreement?"

And it was a rhetorical question, of course, and you knew the moment he put it that he'd made his decision.

And within seconds, it was over.

Presidents grasp at treaties because they convey an image of presidents as statesmen and peacemakers, and they're sometimes not bothered about the details.

It took tremendous discipline for Ronald Reagan to leave that little room without an agreement.

NARRATOR: "I still think we can find a deal," Reagan said.

Gorbachev replied, "I don't know what else I could have done."

♪ ♪ REGAN: He got into the car and his shoulders slumped.

He was in the back seat.

You would have thought that he'd just lost a combination of the Rose Bowl and the Stanley Cup and, uh... the Olympics.

He was so... down.

I've never seen a guy so beat in all my life.

He said... "Don, we were that close," and he held up his left hand-- just finger and thumb, that much.

He said, "We were that close to getting rid of all missiles "and he said he wouldn't give in.

"He kept insisting that we had to do away with S.D.I.

And I couldn't do that."

He said, "I promised the American people I would not give in on that, and I cannot do it."

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: At the time, Reykjavik was considered a failure.

Conservatives criticized Reagan for the deep cuts he was willing to make in nuclear weapons-- for almost giving away the store.

Margaret Thatcher worried he was bargaining away Europe's security.

The mainstream press faulted him for walking away from the most sweeping offer of arms reductions in history-- for sinking a summit by being so stubborn on Star Wars.

Gorbachev stressed the positive.

GORBACHEV: Ya prishyol i zhurnalistam skazal... INTERPRETER: I said to the reporters that, indeed, Reykjavik was a breakthrough, and I said, "Reykjavik will eventually produce results."

And that is exactly what happened.

Without Reykjavik, the process that eventually started and that brought about the one treaty and further treaties-- that would not have been possible.

Reykjavik is really a top of the hill.

And from that top, we saw a great deal.

When Gorbachev visited me at Stanford University after we were both out of office, I said to him, "When you entered office and when I entered office, "the Cold War could not have been colder, "and when we left, it was basically over.

What do you think was the turning point?"

And he said, without any hesitation, just like that, he said, "Reykjavik."

And I said, "Why?"

expecting him to talk about missiles and stuff like that.

He said, "Because for the first time, the two leaders really had "a deep conversation about everything.

"We really exchanged views "and not just about peripheral things; "about the central things.

And that was what was important about Reykjavik."

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Three weeks after Reykjavik, reports from Beirut claimed the Reagan administration had approached Iran with an arms-for-hostage deal.

Reagan denied it.

Could I suggest an appeal to all of you with regard to this-- the speculation, the commenting and all on a story that came out of the Middle East and that... at once has no foundation-- that all of that is making it more difficult for us in our effort to get the other hostages freed.

NARRATOR: Days later, Reagan admitted arms had been shipped to Iran to forge a better relationship, but denied they were arms for hostages.

In spite of the wildly speculative and false stories about arms for hostages and alleged ransom payments, we did not-- repeat, did not-- trade weapons or anything else for hostages.

Nor will we.

Reagan had absolutely convinced himself-- as much as he had convinced himself that S.D.I., once he believed in it, that we had this wonderful system in place-- he had convinced himself that he was not dealing with the kidnappers.

He had promised that he would never deal with the people who had taken the Americans hostage.

He had convinced himself that he was dealing with these Iranian moderates and that he was dealing with the middlemen; he was dealing with the people who were dealing with the kidnappers.

The American middle had been confounded by this patriotic president who had won on standing tall who was found to be paying tribute to the enemy in a kind of a pusillanimous way.

NARRATOR: Reagan had questions to answer.

Good evening.

REPORTER: Mr. President, how would you assess the credibility of your own administration in the light of the prolonged deception of Congress and the public in terms of your secret dealings with Iran, the disinformation?

The record shows that every time an American hostage was released, there had been a major shipment of arms just before that.

Are we all to believe that was just a coincidence?

What would be wrong with saying that a mistake was made on a very high-risk gamble so that you can get on with the next two years?

(chuckles): Because I don't think a mistake was made.

DONALDSON: Ronald Reagan doesn't see the world that you and I see.

He sees a world through rose-colored glasses-- it's a wonderful world, but it's not the real world that exists out there.

And so he didn't want to see a world in which he had traded arms for hostages.

That ran against his grain, that's not his world, yet he did it.

CANNON: Reagan is a classic model of the successful child of an alcoholic.

He doesn't hear things and doesn't see things that he doesn't want to hear and see.

And that's the thing you learn.

You learn that as a child, and Reagan learned it.

NARRATOR: Questions continued to nag Reagan and there was conflicting testimony by others.

Attorney General Ed Meese offered to investigate the matter over the weekend.

Meese insisted on seeing Reagan on Monday.

"I'll add five minutes.

"He's got the Afghanistan freedom fighters coming in, but we'll give you five minutes."

He said, "Okay, five minutes, that's all I need."

So he came in, he said, "Mr. President, I got some bad news for you."

"What's that?"

He said, "There's been a probable diversion of funds "from the arms sales to Iran been diverted to the Contras in Nicaragua."

The president said, "I'll have to clean this up a little bit.

Aw, shoot!"

or words to that effect.

The president actually turned white.

He blanched and he said, "What could have been going through their minds?

Why would they do this?"

NARRATOR: Reagan had asked that the Contras be held together body and soul.

They were-- in a manner which stretched, if not violated, the law.

He said, "We've got to get to the bottom of this immediately and we've got to let the public know."

He was very definite there should be every precaution taken that no one would think that there was any cover-up or any attempt to conceal whatever wrongdoing we might find.

(camera shutters clicking) As I've stated previously, I believe our policy goals toward Iran were well founded.

However, the information brought to my attention yesterday convinced me that in one aspect, implementation of that policy was seriously flawed.

And now I'm going to ask Attorney General Meese to brief you.

Regards the flaw, what was the flaw?

Did you make a mistake in sending arms to Tehran, sir?

No, and I'm not taking any more questions.

In just a second, I'm going to ask Attorney General Meese to brief you on what we presently know of what he has found out.

Will anyone else be let go, sir?

No one was let go; they chose to go.

(reporters shouting out questions) Can I give you att... Attorney General Meese?

(reporters continue shouting out questions) Why don't you say what the flaw is?

MEESE: That's what I'm going to say-- what it's all about.

DONALDSON: How is it that so much of this can go on and the president not know it?

He is the president of the United States.

Why doesn't he know?

Because somebody didn't tell him, that's why.

And to wish everybody else a very happy Thanksgiving day.

REPORTER: Mr. President, who's going to head that commission investigating what happened?

(to turkey): Did you ask a question?

REPORTER: Mr. President, what did you know about money going to the Contras?

All I know is, this is just going to taste wonderful and I'm looking forward to tomorrow.

Mister...

He's not looking forward.

NARRATOR: "I felt I was the one being roasted," Reagan would later quip.

REPORTER 1: Mr. President, how much trouble are you in because of this Contra revelation?

REPORTER 2: Did you know about the Contras, sir?

When will you be able to speak out on this Contra business?

REPORTER 3: Is John Tower going to be the head of your commission?

REPORTER 1: Mr. President, you've never ducked tough questions before.

REPORTER 4: Mr. President, hasn't this damaged your presidency?

NARRATOR: If he knew of the diversion of funds to the Contras, he would be in trouble.

If he did not, he was not in control of his White House staff.

Reagan accepted the resignation of his national security adviser, John Poindexter, who presided over the operation, and fired Oliver North, who ran it.

He resisted Nancy, who wanted to fire George Shultz for not supporting him in public.

But his oldest advisers pressured him to fire Don Regan.

SPENCER: Yeah, Deaver and I told him to get him out of there.

His days were numbered.

You know, he basically said that he wasn't going to sacrifice anybody for, uh... for any of his problems.

I finally said, "You know, I think this has come "to the point where you've got to get rid of somebody "because you've got to do something "that says, 'This is an action I'm taking "'and I'm getting it behind me "and I'm going to go on and do other things.'

"And unless you make a bold move like that, "the media is not going to let you go on, so I think you've got to get rid of somebody."

And he got very angry and said, you know, "I'll be damned if I'm going to throw somebody's ass overboard to save my own."

And for the life of me, I don't know why I said, "Ron," but I said, "Ron, it's not your ass I'm talking about.

It's the country's ass."

And, uh... he looked at me very quietly, and he said, "You know what I think about this country."

And that was the end of the conversation.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Nancy led the battle to get rid of Don Regan.

Reagan could not escape the issue at home or in the Oval Office.

As a child, Reagan had learned to avoid pain by withdrawing.

Now there was nowhere to go.

Nancy and Byron, let's see if we can't turn this cold, dark evening into one of light and warmth.

MAN: I obviously will need information and cooperation and help from the executive branch... MAN: What do you know about the making available to the Nicaraguan resistance of proceeds from the arms sales... MAN: On the advice of my attorneys, I must decline to answer that question at this time.

OLIVER NORTH: Mr. Hamilton, on the advice of counsel, I respectfully decline to answer the question based on my constitutional rights.

MAN: Is there information in the possession of the Justice Department that suggests this thing started earlier?

MAN: There was no smoking gun here.

MAN: That's what everybody is concerned about here-- who knew what and when.

You take one side and I'll take the other... NARRATOR: The shadow of Watergate descended over the White House.

"This presidency is over," columnist Charles Krauthammer wrote.

"1987 will be a Watergate year and the following, an election year."

RON REAGAN: Well, I went to the White House, because it was clear that he was going through some sort of crisis and I just felt that, you know, as his son, as a family member, that I ought to be there, somebody ought to be there that, you know, somebody ought to buck him up and help him get through this.

It was the first time I'd really seen him with the wind completely out of his sails.

One of his greatest assets was the trust of the public.

And when it turned out that in fact there had been an arms-for-hostage deal, the public stopped believing him, at least for a while.

And the polls all showed that, and, you know, he got the polling data every day.

And it became very troubling for him to realize that he was losing the audience in a sense.

That was the first time I got the feeling that he was not able to handle anything that came at him again.

He wasn't quite up to handling a crisis of that dimension.

NARRATOR: In early 1987, the White House grappled with how to extricate Reagan from the worst crisis of his presidency.

Don Regan wanted to get the president on the road to work his charm on the public.

But Reagan was recovering from another serious operation-- this time on his prostate.

Nancy wanted him to stay put.

And that wasn't all.

Nancy's astrologer feared "the malevolent movements of Uranus and Saturn."

The alignment of the planets, it seemed, raised the danger of impeachment and assassination.

REGAN: And in the middle of all of this turmoil, she was incessantly calling me.

One day I got home late from the office.

No dinner-- it was after 9:00.

I was just starting to eat when she called and was on the phone 15 or 20 minutes and we were getting nowhere, about she telling me that I had to do something and I saying, "Nancy, I got to get the president out," or something of that nature.

"He's going to have to be the key here.

None of us can solve this for him."

We went back and forth and back and forth, and finally I was just so disgusted I hung up.

It goes with the turf if you're dealing with the Reagans.

I mean, I knew that back in '65, '66.

And Don Regan, for some reason, took the point of view that Nancy Reagan wasn't important.

That was wrong.

And then, I guess when he hung up her on the phone that was the end of it.

Then we all had to go to work.

My late wife took the call and it supposedly went like this: "Joy, where is Howard?"

According to her, she said to the president, "Howard is at the zoo."

And Ronald Reagan was heard to say, "Wait till he sees the zoo I have in mind for him."

NARRATOR: Don Regan heard that CNN was reporting the president had chosen former senator Howard Baker to replace him.

And I blew my top.

I said, "The hell with it.

"If that's the way they're going to leak about me, I don't want to stay around anymore."

I was so whizzed off at that point that I dashed off a very terse letter to the president: "I hereby resign."

He called me.

Very soft tones, that he didn't mean for this to happen.

He wished it hadn't happened.

And I said, "It's too late.

I'm out of here."

MORRIS: The president should have done it.

The president should have spoken to him personally and said, "Don, I think the time for your long-planned retirement has come."

But Reagan, who was not... who was not good at that kind of human touch when a man's career is coming to an end, simply let the phone lie in its cradle and let other circumstances force Don Regan out-- was derelict in his duty.

NARRATOR: Don Regan had devoted six years of his life to Ronald Reagan.

He never saw him again.

(crowd applauding) MAN: Here, over here!

Over here.

I will be on the job Monday, full-time, and in the meantime Jim Cannon and Tom Griscom will be my transition team.

NARRATOR: What Baker's transition team was told by Don Regan's White House staff that weekend shocked them.

Reagan was "inattentive," "inept," and "lazy," and Baker should be prepared to invoke the 25th Amendment to relieve him of his duties.

(people chattering) ♪ ♪ MORRIS: The incoming Baker people all decided to have a meeting with him on the Monday morning-- their first official meeting with the president-- and to cluster around the table in the cabinet room and watch him very, very closely to see how he behaved, to see if he was indeed losing his mental grip.

They positioned themselves very strategically around the table so they could watch him from various angles, listen to him and check his movements and listen to his words and look into his eyes.

(people chattering) REAGAN: No questions.

We've got to get on with a cabinet meeting here.

REPORTER: When are you giving your speech?

REAGAN: What?

REPORTER: Do you know when you'll give your speech?

REAGAN: Uh... there's a tentative date here.

It has to be first recognized that we can get the time, but, uh, it will be this week.

MORRIS: And I was there when this meeting took place.

And Reagan who was, of course, completely unaware that they were mounting a death watch on him, came in, stimulated by the press of all these new people and performed splendidly.

At the end of the meeting, they figuratively threw up their hands, realizing he was in perfect command of himself.

HOWARD BAKER: Is this president fully in control of his presidency?

Is he alert?

Is he fully engaged?

Is he in contact with the problems?

And I'm telling you-- it's just one day's experience and maybe that's not enough-- but today he was superb.

REPORTER: And Mrs. Reagan?

The issue of Mrs. Reagan's involvement in West Wing decisions?

I haven't talked to Mrs. Reagan today.

I intend to do that later today.

(laughter) I... (laughter continuing) I...

I intend to do that later today, but let me say, I've known Nancy Reagan a long time, too, and I did speak to her on Friday... (phone rings) And I expect that... there's the phone now, so... (laughter) HOWARD BAKER: From moment one at the White House with Ronald Reagan, I came away convinced not only was he fully in com... fully competent, but that he was not being well served by the arrangements at the White House, but that he was fully capable of discharging that job in a very, very effective way.

And I still think that.

MORRIS: He was an old, tired man.

He'd been guilty of neglect of proper supervision of the people who worked for him, but when he was shocked into re-awareness of his job and his duties, he performed as well as ever.

NARRATOR: Reagan was shocked by the findings of a commission he had appointed.

It held him responsible for a lax management style and for trading arms for hostages-- something he still refused to admit.

♪ ♪ One of Howard Baker's first tasks in rescuing the presidency was to get Reagan to admit his mistake.

He found an ally in Nancy Reagan.

CANNON: That's where Nancy Reagan really shines.

She understood that he needed this public credibility.

That's her great role, not getting rid of Regan.

She went beyond protecting him to... to really leading him to this bitter cup of apology that he had to drink from.

A few months ago I told the American people I did not trade arms for hostages.

My heart and my best intentions still tell me that's true, but the facts and the evidence tell me it is not.

As the Tower Board reported, what began as a strategic opening to Iran deteriorated in its implementation into trading arms for hostages.

This runs counter to my own beliefs, to administration policy, and to the original strategy we had in mind.

There are reasons why it happened, but no excuses.

It was a mistake.

But once he'd apologized to the American people and the American people more or less forgave him, you know-- I mean not totally, you know; he was never... he never got back quite the luster, but he... but he got enough of it back that he was able to... that he was able to govern and to be at ease with himself.

I never!

500 points down, Emil.

You said I don't see straight?

502 points down.

NARRATOR: The stock market crashed in October 1987-- another setback for Reagan.

What happened here?!

Oh, sh...!

NARRATOR: Black Monday raised doubts about the soundness of Reagan's economic policies.

♪ ♪ On Reagan's watch, tax revenues would double, but they never kept up with spending.

The national debt nearly tripled.

Although most Americans benefited, the gap between the richest and poorest became a chasm.

Donald Trump and the new billionaires of the 1980s recalled the extravagance of the captains of industry in the 1880s.

There were losers.

The homeless population grew to exceed that of Atlanta.

Reagan seemed indifferent.

AIDS became an epidemic in the 1980s.

Nearly 50,000 died.

Reagan largely ignored it.

In the trying months following the Iran-Contra affair, biographer Edmund Morris had an insider's look at the president.

MORRIS: This was around October of 1987.

He writes in his diary... "Dick and Patty came after dinner and things immediately livened up as soon as they arrived."

That's on a Friday night.

The following day he writes in his diary, "Oh, I was mistaken.

They didn't come down until lunchtime today."

He's talking about his wife's brother and wife-- intimates who visited the White House a lot.

They were members of the family circle.

The schedule said, "Dr. and Mrs. Richard Davis will be joining the first family after dinner tonight."

So Reagan writes it down after dinner as though they showed up.

He says, "Things livened up when they came."

In other words, he was so divorced from reality at that time that he didn't even realize that these people did not show up-- which is funny, but it's also scary.

ANNOUNCER: Ladies and gentlemen, the president of the United States.

(band plays "Hail to the Chief") NARRATOR: Gorbachev's visit two months later was seen during Reagan's presidency as its triumphal moment.

In retrospect, it may have been the first of many.

Gorbachev came to sign a treaty eliminating the intermediate- range missiles in Europe, to accept Reagan's zero option so scorned six years earlier.

At Reykjavik, he had tried to link these reductions to Reagan's giving up S.D.I.

Now, eager for an agreement, he accepted Reagan's terms.

It was over six years ago, November 18, 1981, that I first proposed what would come to be called the "zero option."

It was a simple proposal, one might say disarmingly simple.

(polite laughter and groans) NARRATOR: For the first time in the nuclear age, a treaty would reduce nuclear weapons.

Another, cutting long-range missile forces in half, would be ready for President Bush to sign.

Building up to build down produced results that made the goals of the freeze movement seem modest.

Below.

Oh, yes, that's it.

HOWARD BAKER: It was historic.

And I remember him expressing his pleasure that it was done and I remember him pushing me hard for how the Senate was going to treat it.

But I don't think I ever heard him crow about that.

Thinking back on it, Ronald Reagan never crowed about anything.

I don't think I ever heard him make an immodest statement about his own achievements.

He was a very straightforward and very modest man.

(singing "Moscow Nights") AUDIENCE: ♪ Vsya iz lunnogo serebra... ♪ NARRATOR: The vocal conservatives now wrote off Ronald Reagan.

Columnist George Will accused him of accelerating America's "intellectual disarmament" and "succumbing fully to the arms control chimera."

Others called him a "useful idiot for Soviet propaganda" and an "apologist for Gorbachev."

AUDIENCE: ♪ ... i ne slyshitsya ♪ ♪ V eti tikhie vechera.

♪ (music ends) MORRIS: It was a historic achievement and he was very pleased and happy about it.

But I think he regarded it as an interim step in the progression he was making toward his real goal, which was the elimination of totalitarianism from the surface of the Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Meine Damen und Herren, Mr. Ronald Reagan und Mrs. Nancy Reagan.

(wild cheering) MORRIS: The one thing that Reagan was more passionate about than anything other was the unsupportable phenomenon of totalitarian power enslaving a large part of the world's population.

In other words, what he was really looking forward to was the collapse of Soviet communism.

He wanted to see the wall come down.

Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!

(crowd cheering, shouting and whistling) ♪ ♪ MORRIS: He wanted to see free elections and freedom, liberty, and Christianity in Russia.

It's as simple as that.

NARRATOR: Reagan's "Mission to Moscow" in May 1988 was his final crusade.

It began with a threat that forced the Soviets to let a Jewish couple emigrate.

SHULTZ: He said, "Well, on the way to the Kremlin, "what I'm going to do is go to the apartment "of this couple that you're not allowing to emigrate and visit with them."

With 2,000 press along, you know.

So he said that that's what he intended to do.

By this time, they knew Ronald Reagan well enough to know that if he said that was what he was going to do, he would do it.

He did not, uh... make idle threats.

NARRATOR: The next day, he mortified the Soviets by entertaining 100 dissidents at the U.S. Embassy.

REAGAN: On human rights, on the fundamental dignity of the human person, there can be no relenting.

For now, we must work for more, always more.

NARRATOR: At the Danilov Monastery, he pushed for more religious freedom.

REAGAN: Our people feel it keenly when religious freedom is denied to anyone anywhere, and hope with you that all the many Soviet religious communities will soon be able to practice their religion freely and instruct their children in the fundamentals of their faith.

(bells ringing) NARRATOR: At Moscow State University, Reagan tried to convert the next generation of Soviet leaders with his simple message of freedom.

Your generation is living in one of the most exciting, hopeful times in Soviet history.

It is a time when the first breath of freedom stirs the air and the heart beats to the accelerated rhythm of hope, when the accumulated spiritual energies of a long silence yearn to break free.

We do not know what the conclusion of this will be, of this journey.

But we're hopeful that the promise of reform will be fulfilled.

In this Moscow spring, this May 1988, we may be allowed that hope.

(onlookers applauding) NARRATOR: Until the end, Ronald Reagan tried to undermine the foundations of Communist rule, to preach his dream of freedom.

In his convictions, he never changed.

But his behavior did change.